Theological Premises of TFC Theory — The Theology of the Person

Written by Joseph Clem, M.Ed.

This article does not constitute professional advice or services. All opinions and commentary of the author are his own and are not endorsed by any governing bodies, licensing or certifying boards, companies, or any third-party.

We are who we are because God is Who He is. “The mystery of the Most Holy Trinity is the central mystery of Christian faith and life. It is the mystery of God in himself. It is therefore the source of all the other mysteries of faith, the light that enlightens them” (CCC #234) This especially includes the mystery of the human person made in the image and likeness of God.

For this reason, Jesus gave us a command that corresponds to our being — because He knows why we are who we are. All five transcendentals that have been discussed are revealed through the Greatest Commandment. The first part is “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul [psyche], with all your mind, and with all your strength” (Mk 12:30; also Dt 6:4-5).1 There are alternate phrasings of this among the Gospels, as well as the translation in the Old Testament, but Kreeft (2020) shows how the Old Testament wording (heart, mind, and strength) relates to our affective, cognitive, and volitional capacities (pg. 17, alluding to Dt 6:4-5 — the “Shema” and the “Greatest Commandment” from Jesus). We have feelings, thoughts, and actions. Jesus knows this and commands that we offer up each of these capacities to God. The “soul” would then refer to the body-spirit dynamism. The second part of the Greatest Commandment is “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Mk 12:31; also see Lv 19:18b). This is unity (love of self) and relationality (love of others). Together, they are our heart along with the affection for beauty. Why? Because affection is fulfilled by love – affection that is also informed by truthful cognition and good, free volition.

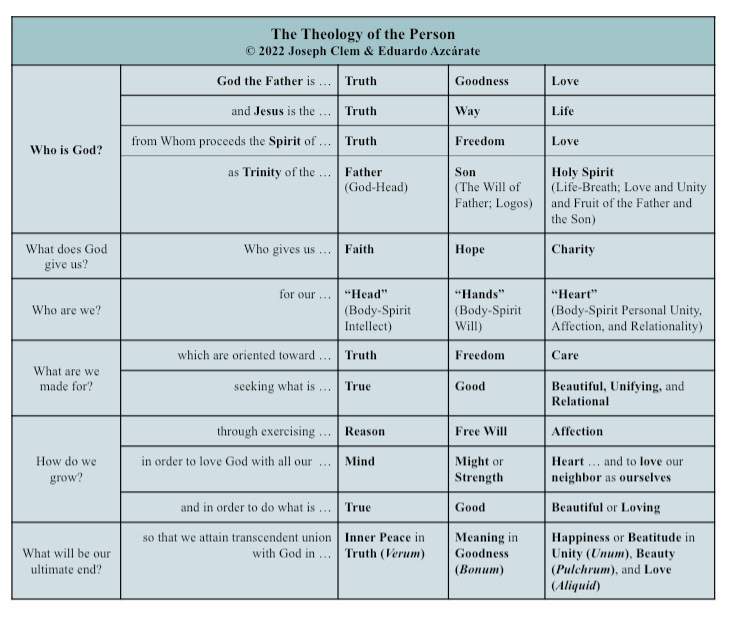

Below this line is content for paid subscribers and includes how the theology of the person is a framework which extends from the nature of God to the nature of the person. The Theology of the Person© [chart] is included.

The closest analogy of which I can relate the heart, the mind, and the will is that our souls are like a flowering plant.2 The heart is the roots, the intellect is the stem, and the will is the flower. The roots are not particularly beautiful but they are the center and the depth of the flower which connects to the direct source of its life which is the earth, though it also depends on the sun and rain which occur without the action of the plant, much like grace (though a flower can actually “face” or lean toward the sun instinctively, and it can preserve water in certain environments that have had a dry spell). In a similar way, our souls get their life from the source of all life which is God. The stem transports the nutrients from the roots to the flower which reflects the beauty within. Our will reveals the beauty of the heart.

The roots branch out from the singular unity of the seed. Why would the seed transform into this relationality with the earth? It has a mission to reveal the beauty within. Beauty is what makes the seed relational and then spring forth out of itself into a blossoming. Our blossoming is a loving action which “stems” from the heart via the mind. The stem brings what is good from the roots to the flower as the mind “translates” what is true, good, and beautiful from the heart to the will so that the will can reflect the truth, goodness, and beauty of the heart. The stem grounds the flower in the earth as the mind grounds the will in reality. Kreeft regards the blossoming as the soul’s beauty, but I would regard it as the soul’s participation in creating beauty which then becomes the starting point again in the heart in regards to affection for beauty. Thus we have a “transcendental life-cycle” of affection for the beautiful to creation of the beautiful to new affection for the created beauty.

The plant connecting with the earth beneath is like how we connect with God. St. Augustine, in his Confessions (401/2017), writes to God: “You were more inward than the most inward place of my heart and loftier than the highest.” (pg. 50, III.VI) Respectively, this is like the nutrients that are received from the roots in the soil (from within rather than from without), but the sun and the rain as grace is received by the plant (from without rather than from within). The plant cannot comprehend the depths of the earth grounding its roots or the heights of the heavens shining and raining down on its petals.

This imagery also corresponds to how Azcárate describes care, truth, and freedom, which correspond to the heart, mind, and will, respectively: “Ultimately, care is at the root — love is at the root — and you build on truth, and then you make the choices” (Azcárate (2022). The choices are our blossoming in freedom from a loving heart and a mind fortified in truth. As will be explored, our body-soul unities have a triune consciousness with cognitive, affective, and volitional intentionalities which co-occur.

… a theology grounded in triune consciousness must proceed. In today’s troubled world a theology that is grounded in the human experience of affectivity and intersubjectivity can seem overly naïve and idealistic, and yet because in such a theology affection is distinct but never separate from cognition and volition, it also may offer a profound hopefulness and a way forward for believers in a world where “the other” is too often feared if not even hated instead of loved.

— Russell (2009), pg. 218

Where is this thoroughly trinitarian theology regarding the philosophical anthropology of the person? Below is an attempt to illustrate such a viewpoint with what I personally feel is a lens by which much of the “cipher” of theology and psychology is decrypted and follows a pattern – the theology of the person.

We come full circle from Who God is, to what we are, to what we ought to do, to what our ultimate aim is in God, and it is all specifically through the marvel of how we have been created by Him. God as Unity, Beauty, and Communion are the Heaven of our affection. God as Truth is the Light of our intellect. God as Goodness is the Freedom of our will.3 “Truth is the relation between being and the mind; goodness is the relation between being and the will; beauty is the relation between being and the heart” (Kreeft, 2020, pg. 293).

Much of the organization of the theology of the person is based on observing patterns across Scripture, Tradition, and the teachings of the Magisterium. For example, freedom, actions, morality, telos, and goodness have a clear connection to the will in Veritatis Splendor.

The relationship between man’s freedom and God‘s law, which has its intimate and living center in the moral conscience, is manifested and realized in human acts … The morality of acts is defined by the relationship of man’s freedom with the authentic good … acting is morally good when the choices of freedom are in conformity with man’s true good and thus express the voluntary ordering of the person towards his ultimate end: God himself, the supreme good in whom man finds his full and perfect happiness.

— John Paul II (1993), #71-72, emphasis added

When we speak about the good, we speak about moral actions’ ultimate aim. When we speak about moral actions, we speak of the exercise of freedom. When we speak about freedom, we speak of freedom for the good. “Only in freedom can man direct himself toward goodness” (Paul VI, 1965, #17). Although truth, freedom, and care interconnect and overlap, each of these corresponding concepts have their best fit under one of these three values.

In Azcárate’s introduction to human sexuality, he remarks, “Whether you are studying the furthest stars and galaxies or the tiniest microscopic cells, you are always probing God’s creation. When studying the human person, God’s most marvelous creation, you realize more fully his majesty” (Azcárate (1997 / 2003), pg. 5). Azcárate never regarded himself as a theologian or philosopher, but by virtue of designing a thoroughly Catholic understanding of psycho-spiritual development, he necessarily points us to these more fundamental truths which we must discuss first – the body-soul dynamic – our overall psychology. It is within the unity (unum) of the body-soul unity and the heart-mind-hands unity that the theology of the person takes place.

Body-Soul Union and Body-Soul-Spirit Distinctions

Azcárate’s psycho-spiritual developmental theory primarily focused on the affection-reason-willpower dynamic (the spiritual form of our psychology rather than the bodily matter of emotions, sensation, and behavior), but first let us discuss the body-soul dynamic.

Catholic tradition has always been firmly rooted in a view of the human person that is both physical and spiritual. Jesus, Himself, asserted the significance of the body in becoming fully human, going through all the stages of physical development, experiencing all human sensations including suffering and death, and resurrecting in a glorified body. Jesus shows us through these mysteries how necessary He believes the body is to be a fully integrated human person. At the same time, Jesus emphasizes the “heart” and the “mind” — the soul — of a person throughout all of His teachings. The soul is eternal and ultimately our present bodies are temporary in this life.

The suffering of the body and of the soul are not as separate as Plato thought. When the body suffers physical pain, there is always a soul-dimension to it. That must be so because the body is always with the soul, at least until it dies: its very being is relative to the soul. It is the body of that soul just as the soul is the soul of that body. And that soul-dimension is always at least somewhat engaged when the body either acts or suffers [receives].

— Kreeft, 2020, pgs. 331-332

Our soul, which is spiritual, will hopefully be in Heaven, albeit as an “incomplete substance” since the soul is “naturally ordained to a body,” yet we will be totally fulfilled in God’s presence, until the resurrection of an eternal, glorified body at the end of time makes us a complete substance again — a complete human again.

Because the soul is ordained to a body, united in a single nature, the soul gains knowledge through the body. “… we are whole beings. Within us, everything is connected to everything else. Body affects soul affects mind affects feelings …” (Azcárate, 2017, pg. 125). This theory requires a bio-psycho-spiritual understanding of the human person in which we examine that relationship in the study of what is commonly referred to as the psyche. For example, “the effects (dispositions and memories) of our previous actions or behavior do not immediately disappear after a change in heart, but commonly continue for sometime” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 284).

Again, we are basically body and soul (spirit), and we are not claiming that we have a third aspect of our nature called the soul (psyche). The psyche is a language-based artificial construct, used in Scripture itself to describe this body-soul (spirit) relationship, which will help us study what is truly a body-soul dynamic working within our body-soul nature. A similar perspective could be that the soul (psyche) exists ontologically, not in the same category as the body and soul (spirit), but rather the real dynamism between the two components of the body-spirit unity — this would preserve the psyche as a real property of each person as opposed to calling it an artificial construct. Yet in either case, we must avoid Hegelian philosophy which equates reality with thought (i.e., my thoughts give meaning to reality as opposed to reality acting upon my mind).

One of the most important passages of Scripture that points to the body-soul unity is when we are briefly described as body, soul, and spirit by St. Paul (1 Thess 5:23). Kreeft, drawing from St. Augustine and Dietrich von Hildebrand, gives an excellent conceptualization that I believe enriches and complements both the CCMMP and TFC Theory by showing how our capacities are bodily, psychological, and spiritual, and also cognitive, volitional, and affective. This creates a “trichotomous three-power map.”

Sometimes the “soul” will be used interchangeably with “spirit” since the soul is more commonly used to describe the spiritual aspect of the person. However, below is an attempt to make the distinction between “soul” and “spirit” but recognizing that there will be language barriers when trying to explain this.

Dr. Bottaro describes this all succinctly when he stated that the overlap of the body and the soul is our “psychology” (Bottaro, 2022). Semantically, it may be more helpful to a wider audience in communicating the dynamic unity of our form (soul) and matter (body) by calling it an “overlap” as Bottaro does. Our “psychology” is actually a study of this hylomorphic union of body and soul. Similarly, Schmitz unpacks the Aristotelian perspective of the vegetative, sensitive, rational soul as layers for how the person is understood.4 The sensitive soul – what we share with animals as a “dimension intermediate between the person’s distinctive features and his corporeal and vital existence” (Schmitz, 2009, pg. 38) – is still not reducible to an animalistic commonality, but rather takes on a personal character by virtue of being a human. The “mind,” “will,” and “heart” are constructs that we use to describe “where” the body-soul dynamism, as a union, occurs. Spiritually, they are the behaviors and experiences of the soul. Etymologically, perhaps the study of the person should be called psychosomatology5 or uni-psycho-somatology, the study of the body-soul union, but we will use the term psychology. I believe the field of Catholic psychology will continue to move in this direction and Azcárate’s Stages of Maturation will advance in its own conceptualization for explaining the body-soul dynamic in relation to how the body physically develops.

The brain, neurotransmitters, hormones, and any other bodily organs or functions constitute the way in which the body impresses upon the soul; while the desires, dispositions, thinking, values, decisive action, and other mental operations constitute actions of the soul that remarkably and reciprocally impress upon the body. Then the subject is further complicated in that these physical and spiritual properties of the mind directly and indirectly impact one another continuously because they are actually “not two natures united, but rather their union forms a single nature” (CCC #366). The inner distress of Jesus’ soul (psyche) led to a bodily reaction of sweating blood (Lk 22:44). The physical healing of the Samaritan leper leads to his interior gratitude which then becomes words of thanks on his lips (Lk 17:11-19). Body and soul cannot act without the influence of the other because to be human is to be body and soul. Every experience (reception) and action (expression) encompasses both body and soul.

Therefore, as all subject matter is considered, it is imperative to remember that the most basic components of a human are a body and a soul, and that other phenomena are names that we have ascribed as artificial constructs through which we can study our total being in an organized and ordered manner. Yet, because the body and soul are both so complex and the complexities are merged into a union, there will always remain a great mystery unto ourselves about our nature, which makes sense since we are made in the image and likeness of a mysterious God. God, in His mercy, speaks to us in terminology which we can more readily understand. God names concepts about our souls with words – words selected based on our limited human language (see CCC #40, 42, 43, 48). He does this throughout Scripture beginning in Genesis with the words “image” and “likeness.” He does this through the ministry of Jesus Christ in referencing the “heart.” He does this through the words of the Saints as they speak of the “intellect” and the “will.” It is important to distinguish that this Augustinian (or Hildebrandian) trichotomy heart, mind, and will differs from the Thomist dichotomy of intellect and will.

Within this book, in order to simplify the language and concepts that are used, the following words will have these corresponding meanings with using a (1) dichotomous understanding of the body-soul union perspective, though the body-soul-spirit perspective is also true, and (2) a trichotomous perspective of the capacities (affective, cognitive, and volitional, each across body and soul):

Body = the physical matter of the person

Soul = the spiritual form of the person (not psyche so as not to confuse with the “body-soul union” and to highlight the dynamic rather than something being “purely spiritual,” though Azcárate’s Stage 6 is primarily spiritual); sometimes used interchangeably with “spirit”

Spirit = also, the spiritual form of the person; sometimes used interchangeably with “soul”

Body-Soul or Body-Spirit Union = the physical-spiritual dynamic of the person

Psyche = also, the physical-spiritual dynamic of the person; the combination of body-soul affection (heart), body-soul cognition (head), and body-soul volition (hands)

Heart = the body-soul union’s center and place of affection for personal unity (includes intrapersonal affection), beauty, and interpersonal relations; includes affective/aesthetic intuition; correlates to the body’s emotions but is not synonymous with the “heart”

Mind or “Head” = the body-soul union’s “mind” and place of cognitive sensing, reasoning, intuiting, and infusion of grace to rise above reason and cognitive intuition in order to receive truth and knowledge; correlates to the body’s sensory-perceptual-cognitive capacity, but is not synonymous with the “mind” or “head”

Will or “Hands” = the body-soul’s “hands” and place of volition (or willpower) and the culminating revelation of the heart and mind; correlates to the behavioral capacity, but is not synonymous with the will or “hands”

Heart, Mind, and Hands

“If heart means feeling, and head means knowing, with both of these subject, directly or indirectly, to willing, then triune consciousness would mean the union of affection, cognition, and volition as an operational synthesis.”

— Tallon (1997), pg. 1

In the late 2010s, I was particularly drawn to the imagery of the heart, mind, and hands as a way to organize the soul. This came from my own experience as a member of Youth Apostles, and at the time discerning to make a lifetime commitment. Youth Apostles has the following Statute to explain our Patron Saints:

We draw inspiration and strength from the spirituality of St. Ignatius of Loyola, as it is expressed in his Spiritual Exercises. His thinking and his style permeate our community and give us philosophical and theological unity. The Ignatian challenge to discernment, determination to follow God's will, avoidance of inordinate attachments, and the wish to always be more and give more are basic to our thinking and our work. We also draw inspiration from St. Francis of Assisi's devotion to the Eucharist, his life of intense prayer, his simplicity, and his deep sense of care for others. St. John Bosco's love and dedication to young people is a further inspiration. His efforts to reach the youth in an effective and creative fashion in order to help them become faithful Christians and good citizens provide additional strength for us to persevere in our ministry tirelessly. Therefore, we believe that the head, heart, and hands of our community are inspired by Saints Ignatius of Loyola, Francis of Assisi and John Bosco.

— Youth Apostles (1979/1989), 1.34, emphases added

One of the great philosophers of our time, Dr. Peter Kreeft, has a beautiful reflection on how are capacities directly relate to Who God is in light of the heart, mind, and hands:

There are three things that will never die: truth, goodness, and beauty. These are the three things we all need, and need absolutely, and know we need, and know we need absolutely. Our minds want not only some truth and some falsehood, but all truth, without limit. Our wills want not only some good and some evil, but all good, without limit. Our desires, imaginations, feelings or hearts want not just some beauty and some ugliness, but all beauty, without limit.

For these are the only three things that we never got bored with, and never will, for all eternity, because they are three attributes of God, and therefore all God’s creation: three transcendental or absolutely universal properties of all reality. All that exists is true, the proper object of the mind. All that exists is good, the proper object of the will. All that exists is beautiful, the proper object of the heart, or feelings, or desires, or sensibilities, or imagination. (This third area is more difficult to define than the first two) …

We are head, hands, and heart. We respond to truth, goodness and beauty. We are this because we are images of God. Each of us is one person with three distinct powers.

— Kreeft (2008/2015), n.p., emphases added

This imagery of “head, hands, and heart” is a popular way to describe what we are as human beings and how we function. Jesus “worked with human hands, He thought with a human mind, acted by human choice and loved with a human heart” (Paul VI, 1965, #22). I posit that it actually points to the deeper reality of how our body-soul unity operates as a trinity of desiring, discerning, and doing.

As observed by a contemporary Eastern Orthodox monk, “With the mind we can think about God, and with the will we can choose to believe in God, but in the heart we can realize and experience God” (Marler, n.d.) The heart is the place of interpersonal encounter (affection), the mind is the discernment of who another person is and how to respond (interpersonal knowledge), and the will is the response (service).

St. Maximus the Confessor, a Doctor of the Catholic Church and revered in the Eastern Orthodox Church, as well, offers a slightly different perspective:

The soul has three powers: the intelligence (mind), the incensive power (heart) and appetitive (will). With our intelligence (mind) we direct our search; with our desire (will) we long for that supernatural goodness which is the object of our search; and with our incensive power (heart) we fight to attain our object. With these powers those who love God cleave to the divine principle of virtue and spiritual knowledge.

— Marler, n.d.

St. Maximus acknowledges the three powers of the soul, but the Eastern perspective is that the heart is more-so the “deep seat" in the soul” rather than feelings. Kreeft also speaks about the heart in this way, in addition to detecting beauty. I believe acknowledging that the heart has a trinitarian role is a possible solution — it is the deepest self, the affective power, and the spiritual place of encounter.

REFERENCES

Augustine (2017). Confessions. Translation by F. J. Sheed (1942/1943). Word on Fire Catholic Ministries: Park Ridge, IL (Original work composed 397-401)

Azcárate, E. M., (2003). The Gift of Human Sexuality: A Christian Perspective [A handbook for parents and teens]. Youth Apostles Institute: McLean, VA (Originally written 1997)

Azcárate, E. M. (2017). Building Truthful Relationships (self-published)

Azcárate, E. M. (2022). Truth, Freedom, and Care [Presentation to Women Youth Apostles]. Blacksburg at Women Youth Apostles Community: Blacksburg, VA (Presented on October 20, 2022)

Bottaro, G. (2022) Episode 82: Changing the Rules: Creating a Catholic Standard for Mental Health. Being Human Podcast. Published July 12, 2022

CCC = Catechism of the Catholic Church (2012). Vatican City, Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana

John Paul II (1993). Veritatis splendor [Encyclical, on certain fundamental questions of the Church’s moral teaching]. Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, Vatican

Kreeft, P. J. (2015). Truth, Good, and Beauty - the Three Transcendentals. Living Bulwark [online publication]. Vol. 81, August/September 2015 (Originally published in 2008 as an essay “Lewis’ Philosophy of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty” in Baggett, Habermas, Walls, & Morris (2008). C.S. Lewis as Philosopher: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty). Accessed via https://www.swordofthespirit.net/bulwark/august2015p23.htm on August 4, 2022

Kreeft, P. J. (2020). Wisdom of the Heart: The Good, True, and the Beautiful at the Center of Us All. TAN Books: Gastonia, NC

Marler, J. (n.d.) Anatomy of the Soul https://www.unseenwarfare.net/anatomy-of-the-soul; 3 Powers of the Soul https://www.unseenwarfare.net/3-powers-of-the-soul

Paul VI (1965). Gaudium et Spes [Vatican II, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World]. Vatican City, Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

Russell, H.A. (2009). The Heart of Rahner: The Theological Implications of Andrew Tallon’s Theory of Triune Consciousness. Marquette University Press: Milwaukee, WI

Sheen, F. (1954). Freedom [televised episode from 1954]. Life is Worth Living [televised series 1952-1965].

Sivik, T. & Schoenfeld, R. (2006). Psychosomatology as a theoretical paradigm of modern psychosomatic medicine [Abstract]. International Congress Series, Vol. 1287, April, pgs. 23-38 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2005.12.051

Tallon, A. (1997). Head and Heart: Affection, Cognition, Volition as Triune Consciousness. Fordham University Press: New York, NY

Vitz, P., Nordling, W. J., & Titus, C. S. (2020). A Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person: Integration with Psychology & Mental Health Practice. Divine Mercy University Press: Sterling, VA

Youth Apostles (1989). General Statutes. Youth Apostles Institute: McLean, VA (Originally drafted 1979-1989)

It is interesting how the scribe who “answered with understanding” responds to Jesus with a shortened repetition of what the Lord says: “to love him with all your heart, with all your understanding, with all your strength” (Mk 12:32-34) which correspond to affection, cognition, and volition in triune consciousness (see Tallon, 1997)

Kreeft (2020) has a slightly different analogy using a plant as an image, as there are most likely others who like to use this imagery.

see Vitz, Nordling & Titus (2020), pg. 418-421, i.e., “we seek ‘freedom for’ positive things that promote our health and development and that cause psychological healing, physical well-being, and moral and spiritual flourishing … positive freedom requires [a] properly formed conscience aimed at an objective good … the person flourishes through a freedom for excellence (positive freedom) that expresses a normative and hierarchical interconnection of the desire and pursuit of existence, goodness and love, truth, beauty, family, and other interpersonal relationships.” (pgs. 418-419); also see John Paul II (1993) in multiple paragraphs, Paul VI (1965) #17, and Sheen (1954)

Schmitz (2009), pgs. 38-47; i.e., “focus on the person in its holistic sense brings out a three-dimensional character of the individual human person that is of particular significance to the philosopher and the psychotherapist. These three dimensions are simultaneously at work in the actuation of our conscious life … Together, these modes of being-present – physical and intellectual (as well as the … sensory mode) — unite to form what was traditionally known as the substantial union of form and matter, of soul and body, and its operative actions.” (pgs. 38, 47)

not to be confused with psychosomatology as the underlying philosophy of psychosomatic medicine, all of which focuses on the mind-body dynamic as non-spiritual (i.e., no soul; the mind is just a mental experience analogous to a secular humanistic perspective); see Sivik & Schoenfeld (2006)