Psychological Premises - Development of the Person

Written by Joseph Clem, M.Ed.

This article does not constitute professional advice or services. All opinions and commentary of the author are his own and are not endorsed by any governing bodies, licensing or certifying boards, companies, or any third-party.

Scope vs. Sequence

We need a thoroughly Catholic perspective on the development of a soul that integrates helpful contributions of psychological and behavioral sciences so that we can perceive the truth of who we are.

Knowing how we develop spiritually and psychologically (which I argue are actually synonymous) is important for us to grow in maturity and to help others grow in maturity. Understanding who we are and how we develop will lead to necessary changes in the methods we use in parenting, spiritual direction, evangelization, youth ministry, catechesis, education, mental health, and many other areas regarding the development of the human person. As will be shown through Truth, Freedom, & Care (TFC) Theory and through supporting theories and evidence, adolescence holds a primary turning point in the development of a person, so caring for adolescent children will be promoted as a primary concern.

Ultimately, the Church has a wealth of wisdom and knowledge regarding the scope of the human person. What we need is a sequence of how we mature; namely, how our intellect grows in apprehending more of what is true, how our will grows in becoming more free, and how our heart grows in being more dominated by love. We know that inner peace, meaning, and happiness are our ultimate end. This section attempts to show how we approach these through a sequence based on truth, freedom, and care.

Will this be about biological, psychological, or spiritual development?

This book is not intended to be a thorough explanation of the biological factors of how we develop, but physiological development matters at every turn. Hormonal changes, physical structures, neurotransmitters, disease, pain, and so many other phenomena affect how we grow. Neurology, neuroscience, and other biomedical fields are necessary for a holistic view of the person.

If the neurologist is concerned with the brain, the psychiatrist or psychologist is concerned with the “mind.” In terms of the mind, or “psyche,” we can still look at our mental processes, language constructs, and even actual behavior through a scientific lens. Human behavior and development do follow natural law and can be studied as such, though this can be a limited perspective if it is not informed by the person’s subjective experience. The field to which this study is most popularly attributed is psychology. However, the term psychology may be interchangeable with related fields that explore mental processes, language, and behavior. Some of the fields include psychiatry, education, behavior analysis, anthropology, sociology, speech-language pathology, and others. Yet, even with a focus on the mind, each of these fields must recognize the biochemistry of the brain to some degree in order to have the fullest picture.

The term “psychology” is actually a Latin-English translation derived from the Greek words psyche and logia – roughly translated as the study of the soul. It is our hope that this original meaning be resurrected so that it is properly understood that studying the mind means studying the soul. Note that St. Paul uses the Greek word psyche (ψυχὴ) when he said “May the God of peace himself make you perfectly holy and may you entirely, spirit, soul, and body, be preserved blameless for the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Thess 5:23).1 He is not suggesting that we are tripartite beings, as is explained by Catholic theologians and Scriptural scholars. However, even St. Paul makes use of this word psyche to differentiate from the spirit (pneuma, πνεῦμα; life-breath).2 In the same way, when we speak of the ego, identity, and similar terms, we are speaking of the psyche in the way St. Paul distinguishes it from pneuma.

Psyche is the word used by Sts. Matthew, Mark, and John when recounting Jesus saying that His “soul” was sorrowful, grieving, and troubled until death (Mt 26:38; Mk 14:34; Jn 12:27). It was the word used to recount Mary’s Magnificat – “My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord” (Lk 1:46). It is one of the words with which Jesus tells us that we should love God when he echoes the Shema: “You shall love the Lord, your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind” (Mt 22:37; Lk 10:27). Yet in that verse, Jesus differentiates the “soul” (psyche) from the “mind” (dianoia) as we do in this theory by equating “mind” with “intellect.”

Therefore, the term “psycho-spiritual,” which is used to describe the type of development covered in this book, refers to the conventional conceptualization of the “psyche” as a spiritual property of an eternal soul. Plainly, “psycho-spiritual” will encompass everything that a person thinks, feels, or does, even though the “psyche” typically only refers to what a person thinks. It is a more integrated perspective to see how a person thinks, feels, and does as a whole so that psychology can truly be a vehicle for growth. What is psychology if nothing else than the therapeutic application of philosophy and theology in order to care for the human soul?

Spiritual Development According to the Saints

Before examining contemporary theories of psychological development, it is important to examine what existed before these: a theory of spiritual development.

It is credible to state that the overall emphasis of the Church and the Saints has been spiritual development rather than psychological development. This makes sense since the psychological and behavioral sciences did not really take full form until the late 1800s and early 1900s. The “psychology” of the Saints was precisely the namesake’s meaning: the study of the soul. In terms of “development,” they examined the growth of holiness. Growth in holiness, rather than a static vision of Christian life, is common to the East and the West. “Catholicism and Eastern Orthodox theology are clearly supportive of spirituality. They both defend a vision requiring the individual to develop his or her response to the grace of adoption in Christ through the Holy Spirit” (Groeschel, 1983/2021, pg. 27). At a deeper level than psychological development, our souls are meant to mature for the sake of becoming the person God wants us to be.

We can see the common stages of spiritual development across the Doctors of the Church, regardless of the language each Saint used to describe the stages.3 It is worth mentioning that spiritual stages are not limited to the Doctors of the Church. Many Saints, in their own writings and examples of their lives, alluded to these stages in more or less direct terms. The stages are now more commonly referred to as the purgative, illuminative, and unitive “ways” or “stages.”

The purgative stage is characterized by the acknowledgement of God as Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier, initial acceptance of God’s love, and the eradication of serious sins in one’s moral life. St. Francis de Sales calls this stage “servile fear.” We believe this is actualized by the effects of Baptism.

The illuminative stage is characterized by several key words: increase, strengthen, and deepen. Whatever was established in the purgative stage is increased, strengthened, and deepened within the context of responding to the call of Christ. By continually putting on the armor of Christ — through the virtues — we are more ready to enter into spiritual battle and cooperate with God’s will. St. Francis de Sales calls this a “mercenary love.” We believe this is actualized by the effects of Confirmation since Confirmation similarly stirs up what has been started in Baptism.

The unitive stage is characterized by profound, loving union with God. It is moving beyond being a “mercenary” for Him in order to become His “spouse” or “beloved.” Love is no longer satisfied with following the will of God alone, but rather wants complete union and identifying with the Person of God, as well. It is a desire to be like Christ that matures into a desire to be one with Christ. We believe this is actualized by the effects of Communion.

These spiritual stages do not account for the psychological development of a person in terms of growing from infancy into childhood, childhood into adolescence, and adolescence into adulthood. Rather, these aspects of development pertain to a relationship with God, relationship with others in degrees of charity, and growing in individual virtues and holiness. There are also corresponding stages of prayer (Dubay, 2002, pgs. 55-91) and stages of morality (Pinckaers, 1985/1995, pgs. 359-374).

Sometimes, we have received insights on the experience of growing up from certain Saints, such as St. Augustine of Hippo or St. Thérèse of Lisieux. We are still left with the task of reconciling the findings of modern psychology with what we know to be the truth and Whom we know to be the Truth. It is a task analogous to understanding recent discoveries about the evolutionary history of humankind in light of God’s primary authorship of creation. In a similar way to how we make sense of fossils and skeletons from millions of years ago, we need to make sense of what psychological studies are revealing about already revealed spiritual truths.

Psychological Development According to Secular Psychology

The fields of physiological, psychological, and behavioral sciences have made significant impacts on our perceptions of the human person, for better or for worse. There is incredible good that has come from those who work in these fields. They can help those who struggle to grow and mature so that they can ultimately live a healthier life. This may include helping people remove sin from their lives, even if the person helping does not recognize it as such. Secular psychology presents many theories coming from different schools of thought. This book is not an endorsement of any secular theory, no matter how often it is quoted; nor are any secular psychologists endorsed. Rather, elements of truth have been found intact, or twisted, among these different psychologists and their theories, so we limit ourselves to taking the good and providing correction as needed from the Catholic anthropological truths regarding the human person.

Below this line is paid content and includes:

A more in-depth conversation on development

A meta-analysis chart which maps out the estimated age ranges of the major developmental theories

There are two main categories of developmental theory in the field of psychology: continuous and discontinuous. Continuous development is the notion that humans develop continuously across quantitative measures, such as physiological measurements and behavioral measurements. Some notable figures that promoted this approach, along with estimated dates of their theories, were:

Edward Thorndike — Law of Effect (1898)

Ivan Pavlov — Classical Conditioning (1906)

John B. Watson — Methodological Behaviorism (1913)

B.F. Skinner — Radical Behaviorism and Behavior Analysis (1945)

Albert Bandura — Social Learning Theory (1963)

Steven C. Hayes — Relational Frame Theory (1985)

Thorndike, Pavlov, Watson, and Skinner were different in that they regarded what they did as empirically natural sciences, such as chemistry or physics. Their work was “atheoretical” and resembled more of a natural science of human behavior. Bandura, Hayes, and others expanded beyond this to examine cognitive processes within a more behavioral model and focus. Continuous development approaches continue to be utilized today in the forms of Applied Behavior Analysis, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and similar therapies that measure behavioral changes, which can include self-reports of internal behaviors and experiences (i.e., thoughts, feelings).

Discontinuous development is the belief that a human being grows through processes that occur in sequential stages. Resolution of a stage is typically expected before moving to the next stage. Unlike continuous development, discontinuous development describes growth more subjectively and qualitatively. Psychologists who use this approach are faced with the challenge of describing stages that are universal, not necessarily stages that are specific to a certain culture, sex, or system of beliefs. In terms of personality development, which TFC Theory might be mostly defined as from a secular psychology perspective, “only Freud and Erikson provided a theory” to explain this, “and only Erikson included early adulthood” (Vitz, Nordling, and Titus (2020), pg. 62). What is interesting is that there is an evolution of theory from Freud’s psycho-sexual stages (1905) to Erikson’s psycho-social stages (1959) to Azcárate’s psycho-spiritual stages (1979).

Each of these theories offers some perspective on the mystery of the human person. However, more recent literature and research build up on and add insights to the theories that have been listed. For example, the Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person (CCMMP) acknowledges that Kohlberg and Piaget have made contributions to understanding moral cognition, but they argue that “they have in various ways been critiqued and surpassed by Hoffman (2001) in understanding empathy” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 291).4 We always need to be open to new findings and conceptualizations so that we continually improve our therapeutic models. It is worth noting that there is agreement across multiple disciplines that adolescence, especially around 12 years old, is the advent of seismic developmental changes.

There are different schools of thought and ways of organizing the various aspects of human development, each with their own emphasis. It sometimes includes a completely different philosophy or worldview. They are loosely categorized into the following strains of thought:

Psychodynamic & Personality: resolve conflict in the “subconscious” and “unconscious” mind

Behavioral: resolve conflict in the stimulus-response relationship and behavioral contingencies for both public (outer) and private (inner) behaviors

Existential & Humanistic: resolve conflict in the unique perception of the self and the meaning of one’s own life

Cognitive: resolve conflict in thought patterns

Evolutionary, Biological, & Neurological: resolve conflict that is physiological / bodily / hereditary

Attachment: resolve conflict in attachment styles / patterns of relating to other people

Sociocultural: resolve conflict related to society, culture, and family dynamics

Each theory should be taken seriously. Different perspectives can help enhance the perspectives of others. Reflecting on the limitations of psychoanalysis, the psychoanalyst Erik Erikson shares the following insight as one example of this importance:

The traditional psychoanalytic method … cannot quite grasp identity because it has not developed terms to conceptualize the environment. Certain habits of psychoanalytic theorizing, habits of designating the environment as “outer world” or “object world,“ cannot take account of the environment as a pervasive actuality. One methodological precondition, then, for grasping identity would be a psychoanalysis sophisticated enough to include the environment; the other would be a social psychology which is psychoanalytically sophisticated; together they would obviously institute a new field which would have to create its own historical sophistication.

— Erikson (1968), pg. 24 (emphasis added)

Erikson is suggesting here that even his own field does not provide a full account of the study of the person. B.F. Skinner acknowledged that private behaviors (i.e., thoughts) existed and followed the same rules of behavior that he identified regarding observable (public) behavior; however he said we lacked the “technology” to observe these private behaviors. The limitations of each field can be daunting for a clinician of any of these disciplines. What ends up happening is that continuing education is being required across disciplines which seek to integrate necessary information from other fields so that they all become “interdisciplinary” experts. Indeed, modern psychological theories have been described as “partial theories of the person” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, p. xi) This is quite the task for a clinician that attempts to integrate relevant approaches for his or her patient. It may not be necessary to be an expert on everything, but this points to the reality that every approach is limited in unraveling the complexity and mystery of the human person. It is not hopeless for a clinician to make a significant impact, but he or she does need to be an expert on what we are as body-soul unions, how we grow beyond where we are, and what the end goal for the patient should be.

From our own Catholic perspective, we already know that secular theories should be taken with great caution. The underlying philosophy is not always consistent with the truth of who the human person is as a creation of God and endowed with an immortal soul. Some secular fields adhere to the “religious” beliefs of scientism and naturalism in which only the findings of science and what is readily observed through the physical senses can be regarded as truth. Although there are many theories on human development, and many elements of the truth can be found in each of the theories, the wholeness of the truth can only be approached by examining the human person as both body and soul through the lens of our Catholic faith. Therefore, it is our belief that secular theories, both the continuous and discontinuous theories of development, should be considered.

Beyond theories of our development based on age, learning and development cannot be separated. In terms of the nature vs. nurture debate, one might say that aging (natural course of body and psychology) refers to our nature and that learning (becoming more than what we are currently) refers to our nurture.

Educational Perspectives

St. John Bosco

Certainly, St. John Bosco, known for his “Preventive Method,” is a champion for integrating the heart into the importance of education when he says “education is a matter of the heart” (Avallone, 1999). Not coincidentally, he is another Patron Saint of Youth Apostles, of which Azcárate is the founder. He regards reason, religion, and loving kindness as the three major components to bringing young people to Christ. Azcárate’s community of Youth Apostles adopted this Preventive Method of St. John Bosco because it aligned with truth, freedom, and care. We guide a young person to reason toward truth with his or her intellect. We provide a young person with religion to orient his or her will toward freedom. We express loving kindness as an affectionate expression of care to enter into relationship with the heart of the young person.

Secular Education

From a secular perspective alone, even researchers, clinicians, educators, and others can see the importance of integrating three aspects of the person along which he or she grows – cognition, volition, and affection. A unique study in the educational field measured outcomes based on examining cognition, volition, and motivation-affection as independent variables. The study claimed that although the three aspects were not necessarily predictive of academic achievement since “mechanical and repetitious learning also lead to high grades,” the researchers said that cognition, volition, and motivation-affective “account for deep learning” (Valle, et. al., 2003, pg. 575) Deep learning, here, refers to “deep information processing [cognitively], which in turn leads students to assume responsibility, display high levels of persistence, perseverance, and the tenacity [volitionally] to achieve the aim of this motivational orientation” which is to have a positive self-concept of intelligence, ability, internal attribution for success, and reflecting on past achievements (self-affectively) (Valle, et. al, 2003, pgs. 575-576). In terms of the philosophy and theology of the person already discussed, the motivational-affective component in this study would be intrapersonal affection (perceived self-worth) which is critical to TFC Theory. It would be fascinating if interpersonal affection, such as in the power of a relationship to parents (indirect) and of a relationship to a teacher (direct), were included in this type of study for future research.

More content coming regarding Maria Montessori …

Grounded in a Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person

The Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person (CCMMP) is a recent framework from psychologists, philosophers, and theologians at Divine Mercy University (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020). Through that framework, one can see the different psychological aspects of a person in light of philosophy and theology. It is our hope that Truth, Freedom, and Care (TFC) Theory can provide a possible developmental sequence that builds upon and complements the CCMMP which also draws upon examining the person as rational, and volitional/free. The CCMMP states the following regarding a developmental perspective:

People develop their multiple capacities of human nature overtime through physical growth and relationships (especially those relationships that involve family, marriage, friends, society, and religion), moral practices and decisions (through which the person seeks to be just and to contribute to the common good), and virtues and vocations (through which the person overcomes a divided heart, social discord, and religious indifference, as well as participate in flourishing and communion).

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 271; referencing Rist, J. (2009), pgs. 22-41

Virtues are necessarily connective and developmental. Each virtue needs to be completed through a developmental interconnection of the virtues.

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 279

The CCMMP also describes development in this way:

The person comes into existence when his or her living body-soul unity comes into existence at conception. The unfolding of the multiple capacities of human nature is subject to development over time through biological growth as well as through family and social experiences, which prepare for growth understood in terms of virtues and vocations. This mature development is manifest in relationships, especially marriage and family, friends and community, work and service, and religion. Through this moral and spiritual development, the person seeks to overcome a divided heart, social discord, and religious indifference.

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 30

Generally all of childhood and adolescence are spent in the single state of life, in which the child or adolescent is called to obedience and honoring of parents, to serving as a role model for siblings, to developing friendships with siblings and peers, to work at attaining an education and skills, as well as to other service to the family through chores. Children are also called to age-appropriate leisure, which is normally a form of play. At all ages they are called to relationship with God and goodness, and they are called to develop virtues. During the time of maturation, as well as throughout one’s life, being single is a foundational state full of potential, development, and flourishing. The foundational state of being single informs ethical, family, and social responsibilities and opportunities, for it marks out the ways of being in the world and for others.

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 222

Through this description, we see the importance of biological, relational, moral, and spiritual development for a comprehensive understanding of the person as an integrated whole. We cannot reduce a person to only one of these. We are, in a summary of the CCMMP, a body-soul union, as male or female, sensory-perceptive-cognitive, emotional, interpersonally relational, rational, volitional beings who are fulfilled through virtue and vocation. Although TFC Theory predates this framework, it readily adopts and embraces it as a fundamental basis for understanding the person. Also, the theological premises of the CCMMP as the person being created, fallen, and redeemed, aligns TFC Theory with the most basic, Catholic narrative of the person. Fr. Benedict Groeschel foreshadows this outline with the following: “The Fathers and Doctors of the Church have consistently taught that human nature, though wounded, is good. The human being can be saved only by Christ who comes as the sower seeming good ground and as the bridegroom of the parables demanding some response of acceptance” (Groeschel (1983/2021), pg. 26). Elsewhere, Fr. Groeschel describes maturation vs. estrangement as the following:

Human beings are in a constant process of becoming. When we are moving or becoming in an appropriate way, we are growing. When we cease to grow or to be involved in a dynamic process of becoming more creative and more productive, we are in a negative process of becoming, or a decline.

— Groeschel (1983/2021), pg. 40

Although TFC theory is not specifically on ethics, I believe the ethical vision of the CCMMP points to our common premise as Catholics. The CCMMP calls its ethical approach prudential personalism, which is described as “rooted in the basic human experience of the need for relationships and personal reason, will, and emotion in moral agency or behavior” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020)., pg. 259, emphasis added).5 In TFC Theory, the heart (relationships and emotions), the mind (reason and sensation-perception-cognition), and the hands (will and behavior) are the basis for understanding our actions, and therefore, our development!

Now the question becomes: how do these aspects of the person develop individually and as a whole from conception to adulthood? The nuances of development up until the beginning of adulthood cannot be taken for granted. Furthermore, how does each aspect develop? What is the roadmap? Azcárate proposed in 1979 that the rational, volitional, and affective aspects of our humanity ultimately grow toward the values of truth, freedom, and care (i.e., love, self-gift). This resonates with the comprehensive premises of the CCMMP.

First our reason is meant for truth: “Humans have rational inclinations to seek and know the truth and to find flourishing” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 40, emphasis added). The “rational capacity … flourish[es] by seeking truth about self, others, the external world, and transcendent meaning” (Ibid., pg. 44, emphasis added). “Because of the importance given the truth, as expressed in the words of Christ ‘I am the way, and the truth, and the life,’ reason was understood as central to personality from the beginning of the faith. The Gospel writers in Saint Paul also spoke frequently of speaking and knowing the truth” (Ibid., pg. 69, emphasis added).6 Even reason’s bodily parallel of sensation-perception-cognition is ultimately oriented toward truth – toward sensing and perceiving reality as it is and judging it to be so.

Second, our willpower is meant for freedom: The CCMMP describes the will’s aim as this: “True freedom … is an expression of the whole person” (Ibid., pg. 42). The implication here is that when freedom is limited - anything impacting our will - then the whole person is not expressed in action. It is also not merely a freedom from the things that inhibit us, but also a “freedom for excellence” (Ibid.). This certainly goes beyond Skinner’s reductionist perspective of freedom as solely an experiential freedom from control.7

Third, our passions and interpersonal affections are meant for experiencing and expressing love. “In terms of morality, depending on the way [emotions] relate to love, reason, choice, truth, and flourishing of self and others, emotions can become good or evil” (Ibid., pg. 37, empahsis added). Elsewhere throughout the CCMMP, emotions are rightly understood as progressively conforming toward actual truth, actual goodness, and actual beauty in healthy development. Although many ideals are listed that determine the health of an emotion, we believe that we are ultimately working toward love itself - to have our desires and affection dominated by love. We even influence our emotions indirectly over time through self-knowledge (Ibid., pg. 41). God wants us to orient our passions and relationships towards love because He is Love Itself as He is Truth, Goodness, and Beauty.

The person is centered in love, which is the most basic of human dispositions and actions … the highest expression of interpersonal communication is centered in love … It is symbolized, in the spiritual and romantic traditions, as emanating from the ‘heart’ or the center of the person … In the fullest sense, including the diverse kinds of human knowledge and affect, love perfects the will and other affective capacities as love perfects the whole person interpersonally.

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pgs. 312, 313, 315, emphasis added

Truth, freedom, and interpersonal love are the guiding stars by which we develop.

An important distinction is that the CCMMP is not a rubric for evangelization. It explicitly states that it is rather a framework for mental health practitioners who may or may not have Catholic clients. “The Meta-Model itself … provides a normative understanding of the nature of the person, which guides clinical understanding without being a clinical theory itself” (Ibid., pg. 571). I believe TFC Theory is a cogent theory that is consistent within this “normative understanding” of human nature.

TFC theory has found its fullest application in the context of evangelization since 1974 with the a single-sex, parish-based youth ministry, based on these values, begun by Azcárate and a fellow volunteer, Beatriz Hernández, who moderated the girls’ group which began the year prior.8 TFC theory has always intended to help a person grow beyond secular virtues into an actual Christocentric relationship with God. It is in the context of this relationship that secular virtues and values become Christian virtues and values. True growth and development necessitates a relationship of faith, hope, and love with God. Ultimately, the terms maturation and estrangement were decided upon to distinguish between healthy and unhealthy development of the person.

Maturation Points to Truth, Freedom, and Care

In an article featured in an article from March 1973, Azcárate and Hernandez gave a vision of maturation of young people in the Church:

We must continually encourage each other to seek ultimate values in our lives. We want to be open, develop a sense of trust and live in the truth where faith can develop. We want to make responsible choices and live in the freedom where hope can develop. We want to sacrifice ourselves for the other and live a life of mutual care where true love can develop. Faith, hope, and love, and the greatest of these is love.

— Azcárate & Hernandez (1973), pg. 20

Here are some descriptors of what we mean by “maturation:”

Developing according to our human nature

Integration of body, mind, and soul

Progressing in areas of reason, willpower, and affection

Becoming what God wants us to become: what we ought to be, according to His image and likeness and to the unique mission that He has for us.

Leads to virtue and holiness within one’s vocation;

This maturation of our bio-psycho-spiritual development is parallel to our bodily development, cognitive development, and our spiritual development across the conventional stages identified by the Doctors of the Church: purgation of sins, illumination of God’s will for us, and union with God Himself.9

The antonyms of the word “estrangement” are “unity” and “reconciliation”

The CCMMP describes maturation as communion with God, communion with others, fulfillment through virtue, fulfillment through vocation and interpersonal relations, and integration of sensory-perception/cognition, reason, emotion, and will (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pgs. 20-44). In the community of Youth Apostles and in other places, the imagery of the heart, head, and hands are used to convey this deeper reality of having a heart, intellect, and will.

King of glory, Lord of power and might, cleanse our hearts from all sin, preserve the innocence of our hands, and keep our minds from vanity, so that we may deserve your blessing in your holy place.

— Christian Prayer (1976), pg. 729 [psalm prayer for Ps 24]

Our hearts, heads, and hands all need redemption.

It bears repeating how we are made for God – our intellect is made for truth to live in Truth, our will is made for freedom for Goodness, and our heart is made for love of Beauty. We are made for the true, good, and beautiful. We are made for truth, freedom, and care.

If we always do that which is most caring, most loving to ourselves and others, and if we always do it being truthful to ourselves and others, then we will achieve true freedom … His command is to love - if we truly love, then we will come to know the truth and live in truth; and if we live in truth, then we will do what is right and we will be free.

— Azcárate (2017), pg. 190

We do not have three diverse ends – we have one end which is the “universal good,” or “Divine Will” (see Aquinas, 1273/2017, II-I, 1.1, 1.3-1.5) – but truth, freedom, and care are core end-states that point to our one true origin, our one fulfillment in this life, and our one beatitude for eternity. Just as intellect, will, and heart keep co-occurring, so do their corresponding values of truth, freedom, and care.

Estrangement Points to Lies, Self-Imprisonment, and Selfishness

Estrangement is a form of evil in the sense of “a loss, privation, disorder, or lack of something that should properly belong to a person or a thing” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 390). In the cosmic battle between good and evil, the evil one recognizes that goodness is truth and love. Therefore, he pits truth against love, and love against truth, in almost every battle that we have with ourselves and with one another. In seemingly pitting these against one another, and against freedom, they are not actually the co-existing values but rather distortions which we perceive to be incompatible. Lies are incompatible with love because love and truth are actually the same. Selfishness is incompatible with freedom because love and freedom are actually the same.

As the history of the human race shows, our humanity has descended too often into inhumanity (marring our essential nature), as division disrupts unity (unum) and deranges our innate relationality and community (aliquid), as we introduce falsity into truth (verum), evil into good (bonum), and the ugly into the beautiful (pulchrum).

— Schmitz, 2009, pg. 34

Estrangement includes “psychological disorder … caused by (a) developmental and neurological disorders; (b) abuse and trauma; (c) one’s own present choices; and (d) the effect of one’s past choices and vice” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 289). It also includes “moral and spiritual evil” as “the voluntary thoughts, words, or deeds that are against reason and human nature or that counter the natural and divine law” (i.e., sin) (Ibid.).10

Part of the reason estrangement occurs is that it is the easier path. “The road of virtue is uphill, and often quite steep, whereas the road of vice is downhill, sometimes with a barely perceptible, downward slope to it” (Azcárate, 2017, pg. 108).

Here are some descriptors of what we mean by “estrangement:”

Estrangement from our human nature and our purpose as creatures of the Creator

Estrangement from the human family; turning inward; closed up; pride as the root of all sin

Estrangement from God

Clouded reason, weak willpower, and defective interpersonal and intrapersonal affection; the Catechism refers to sin as an “abuse of our freedom” (CCC #1733).

Disaffection (or displeasure) for the true, good, and beautiful

“A lack of the moral ordering that should be found in human inclinations, cognition, affection, actions, and relationships” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 478)

Animalizing ourselves by becoming enslaved to our passions, by becoming irrational, and by removing our free will (i.e., through drugs and alcohol)

Leads to cycling of sin

When we do not mature forward in resolution of our conflicts, we stagnate or even retrogress in our development.

In describing the consequences of sin from the theological perspective, the CCMMP provides a succinct description of estrangement: “mankind against God, each human person, against himself, person against person, and mankind against nature.” They go on to describe how evil affects us across each of our capacities: “emotions (hatred), thoughts (lies), choices (harming self or others), commitments (adultery instead of fidelity) or development (failures to develop one’s human capacities or to fulfill other responsibilities).” This estrangement should not come as a surprise and is unfortunately expected to exist to some degree within every person due to our proclivity to sin called “concupiscence - disordered emotions [and] weakness of reason and will” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pgs. 22-24)

Just as maturation is related to virtues, estrangement is related to vice. “Vice is contrary to man’s nature, and as much as he is a rational animal: and when a thing acts contrary to its nature, that which is natural to it is corrupted little by little.” (Aquinas, 1273/2017, II.II.34.5). The CCMMP describes humans as either flourishing or languishing. They describe languishing as:

… the result of giving in to indifference, despair, short-sightedness, fear, distrust, impatience, avoidance, intransigence, and especially self-centeredness. Languishing involves a disintegrative movement of the person who suffers from the negative influence of such actions and attitudes on his own development and interpersonal relationships.

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 250

The descent into estrangement ultimately can be understood as a deterioration and distortion of our cognitive, volitional, and affective powers. In Monsignor Pope’s reflection on one of St. Bernard’s sermons, he explains how a person goes through stages of sin (Pope, 2016).11 Regarding affection, St. Bernard says that sin “paralyzes the affections” to which Msgr. Pope replies: “The first thing we lose is our desire for spiritual things.” The proceeding stages of sin according to St. Bernard are concerned with thoughts (i.e., “unsteadies the light of judgment,” “a rigor of the mind takes over,” and “reason is lulled to sleep”) and the will (i.e., “vigor slackens” and “energies grow languid”). Notably, Msgr. Pope explicitly describes the loss of reason and will as “our thoughts becom[ing] distorted” and “lack[ing] strength to do good,” respectively. Then, there is a destructive cycle of darkening, clouding, distorting, atrophying, and imbalancing of the faculties of the person.

Following the model of rational, volitional, and affective powers of the person, the antitheses of truth, freedom, and care should be examined as fundamental elements of estrangement: lies, self-imprisonment, and selfishness.

Mowrer,12 who influenced Dr. Tyrell’s use of truthfulness, freedom, and care in therapy, had an earlier form called Integrity Groups which identified the disvalues opposite to the values:

Note the … basic principles of honesty, responsibility, and involvement which are stressed in Integrity Groups and the resulting ability to “get in touch” both with one’s own feelings and with other human beings. (Mowrer, 1970, pg. 11)

In Integrity Groups our assumption is that human beings become alienated (lose community) because of the practice of dishonesty, irresponsibility, and [emotional or relational] uninvolvement. (Ibid., pg. 28)

The disvalues unsurprisingly correspond to Azcárate’s anti-values in TFC Theory – lies (dishonesty), self-imprisonment (irresponsibility), and selfishness (relational uninvolvement).

Truth, Freedom, and Care Theory

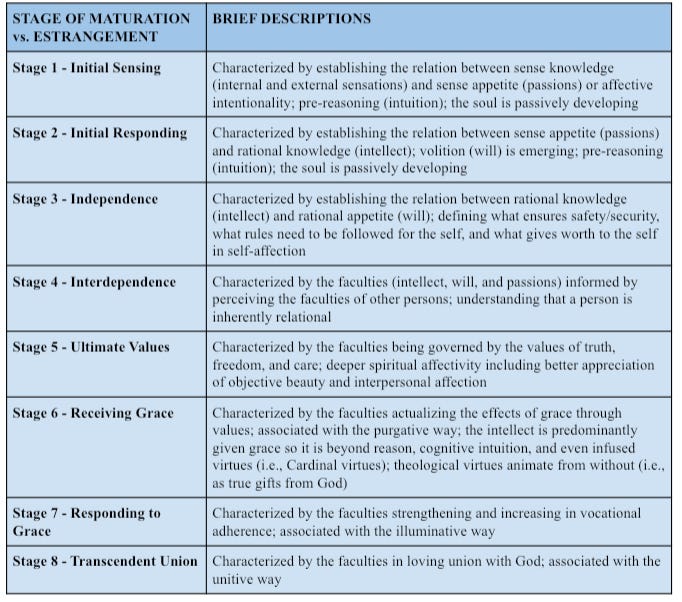

The theory behind the Maturation vs. Estrangement Growth Chart, originally conceived by Dr. Azcárate in the 1970s, is that “child, adolescent, and adult development occurs in eight stages of psycho-spiritual development across three different areas of development in each stage” (Azcárate, 2020). The three areas are aspects of the soul - the intellect, the will, and the heart - which are connected with and “hinge” upon truthfulness, freedom, and care as ultimate values that help a person grow from immaturity to maturity. “Therefore the theory can also be referred to as the Truth, Freedom and Care (TFC) Theory” (Ibid.). The framework, or organization of the stages is very similar to Erikson’s psychosocial stages of which the CCMMP makes an interesting distinction:

Secular theories of personality seldom mention the traditional virtues … An important exception was Erik Erickson, who introduced virtues (or ego strengths) into his eight psychosocial stages of development. Erickson anticipated, along with some of the concepts associated with the self-actualization of Maslow, the present positive psychology movement that has brought virtues back into contemporary psychology.

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 6913

“Like Erikson’s stages, each stage is presented as opposite ends of a possible resolution scale for each stage” (Azcárate, 2020) One end represents a behavioral repertoire and internal experience that pursues value. The other end represents the behavioral repertoire that moves away from virtues, values, and ideals.14 They are sometimes vices, but more broadly they are either the absence or twisting of the good.

For example, awareness vs. aloofness represents the two extremes of a continuum. Someone may be more aware or more aloof but the positive resolution of each stage means that the person will end on the awareness rather than aloofness end of the continuum as will be explained below.

— Azcárate (2020)

An important note: these issues occur naturally as part of our human condition as fallen in a theological sense. “Because of the sin of Adam and Eve, the divine likeness in mankind is wounded and disfigured” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, pg. 22). These issues are not necessarily indicative of something pathological, diagnosable, or neurological / physical. However, they are not what we are created for. We have been created to praise, reverence, and serve God, and by this means save [our] soul[s]” (Ignatius, 1524 / 1961, SE #23). Therefore, in having issues of imperfect maturation or growing out of estrangement, no matter how severe, we need to remember that “no one has had a perfect development, for we were all born into a fallen and wounded world; we will find defects and deficiencies all the way through” (Groeschel 1983/2021, pg. 44).

Another relevance that Erikson had was how he incorporated the pursuit of interpersonal relations into his psychosocial development. The CCMMP specifically points out that Erikson “construes human growth as progressing in stages from individuality toward mutuality and, finally, community, where love finds a fuller expression” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 315, referencing Erikson, 1968).

One way the values may be understood is that they are ethics of our reason, morality of our will, and the ethos of our heart. A behaviorist may call these rules which evoke rule-governed behaviors or macro-repertoires of behavior that have been learned over time. However, we as Catholics understand that ethics, morality, ethos, rules, guiding principles, etc. are not arbitrarily defined and are not necessarily in the eye of the beholder if one is to actually flourish and healthily develop.

Maturation vs. Estrangement is a semi-discontinuous theory of development since there are distinct stages but a high degree of fluidity in how the stages are revisited as an individual and in interpersonal relationships. Stages 1-4 may be called “prematurity”, while stages 5-8 may be called “maturity.”

All of the stages relate to truthfulness, freedom, and care either directly or indirectly – as a prerequisite skill or as a full realization or outcome of a life lived according to those values. Truthfulness relates to reason (a faculty of intellect knowledge); freedom relates to will (a faculty of intellectual appetite); and care relates to interpersonal and intrapersonal relations through affection (a faculty of the heart). “The Maturation Chart assumes that truth, freedom, and care overlap between stages and also inter-relatedly between these three different areas of development within each stage” (Azcárate, 2020).

The stages of maturation are labeled according to a psycho-spiritual focus, but the stages are also informed by developmental models that consider the physical development of the person. Each person is unique and complex by our nature as body and soul. This requires an integrated, flexible, and multi-dimensional lens through which to examine the development of the psyche. Although approximate ages are given for the stages of maturation, it is theorized that a person can:

Work to resolve a stage outside of the age-estimated sequence

Work to resolve two or more stages concurrently, in part or in whole

Revisit an earlier stage in order to have a more complete resolution for the purpose of more healthily resolving a later stage or revisiting it for the purposes of discovering a new dimension of the stage by virtue of maturation in other areas

Have an experience that disrupts a previously resolved stage

Always be working toward ultimate values of truth, freedom, and care as terminal (ultimate) values

Manifest issues of a virtue / value, depending on the context, as imbalances (“excesses” and “deficiencies”) of reason, will, and emotion regarding the virtue / value. For example, a person who weaponizes the truth in order to harm someone is not necessarily lacking truth, but has an imbalance in which he/she lacks the interpersonal affection of care.15

Demonstrate some behavioral patterns that are components of a larger repertoire representative of a future stage no matter how far away (thus a belief in continuous development as well as discontinuous development)

Go through these stages, not just as an individual person’s development, but as a relationship’s development with another person, group of persons, and with God (i.e., spiritual development)

We can see from nature and from research that age is a predominantly influencing factor for some biological and cognitive processes. We can also see that certain spiritual processes do not typically occur until later in life. “… children have a limited capacity to hear and understand the truth depending on age, intellectual development, sensitivity, and other personality characteristics. If a child is not ready to hear the whole truth, he or she will only hear what they are ready to process” (Azcárate, 2017, pg. 181). In terms of the age estimates:

They should be understood as a flexible estimate.

We need a general sense of when these processes predominantly happen so we can more precisely help a person grow — a help that is informed by the age of the person.

There is a major short-sightedness from secular psychological development models. If we truly believe that a person is a body-soul unity, then we must acknowledge the development of the soul that occurs before birth. Major experiences have occurred prenatally and have only more recently come to light. Something as simple as thumb-sucking in the womb helps a person to be prepared to find the breast of the mother. Learning to distinguish between a voice that is heard often versus a voice that is heard seldom, as evidenced through a prenatal child’s reactions to the voice of a mother or father, helps prepare a person to gravitate toward the voice of a parent after being born and to pair that voice with a smile and a touch. Much of what occurs may remain a mystery, but one only has to look at the consequences of prenatal development to see just how much of an impact it truly has, for better or for worse. TFC Theory was originally conceived as postnatal development by Azcárate (1979), but I proposed to extend this to re-conceptualize the first stage of development (“Initial Sensing”) to encompass human conception to the postnatal age of about two. As stated in the CCMMP, “From conception, persons move toward the good, and in time, with adequate development, actively seek it. They also begin to concretely respond to the call of values and goodness in their lives …” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 229, emphasis added).

The implication here is that the onset of a stage occurs at some point in a person’s development, but the stage is ever-present throughout a person's life, regardless of whether or not it is being actively resolved. It shapes and forms its subsequent stage and continues to do so for a lifetime. A foundation is not removed merely because the rest of the building has been erected.

Values are polemic (the ideal being at one end and the anti-value at the other end) while virtues are moderating (the ideal being the moderation of reason, will, and affection). The challenge is that some of the stages necessarily describe both a value and a virtue which requires both a polemic and moderating perspective. Furthermore, no value (or virtue) can truly be examined within only its respective domain (i.e., reason, will, or affection) since there is always a need for integrating all domains (i.e., for each of the 24 values). “Since the three different areas [of reason, will, and affection] overlap, the division is an artificial construct to facilitate the study of each one. However, a positive resolution of each area is necessary to most successfully move into the next stage” and to have a higher likelihood of resolving that next stage (Azcárate, 2020).

Comparison to Other Theories

In looking at other theories, it is important to examine them as just that — theories. My hope is that there is an air of humility and philosophic doubt with Truth, Freedom, and Care Theory so that it is allowed to evolve and unfold in the future as more information and insights are discovered and gathered.

The psychologist Fr. Benedict Groeschel, CFR shares his own thoughts about human development. In his book, Spiritual Passages: The Psychology of Spiritual Development (1983/2021), he leans heavily on Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stages as Azcárate did, as well. Fr. Groeschel also emphasized religious development as a natural virtue that grows with age, and he emphasized “The Three Ways” (purgative, illuminative, unitive).

The age estimates were partly based on preliminary thoughts from Azcárate about when he believed the onset of certain stages began. In looking through the other theories and attempting to balance the findings and agreements among multiple disciplines, the following age estimates were given:

Stage One: Conception to two years old

Stage Two: 2 to 5 or 6 years old

Stage Three: 5 or 6 to 11 or 12 years old

Stage Four: 11 or 12 to 15 years old

Stages Five and Six: 15 to 18 years old

Stage Seven: 18 to 24 or 25 years old

Stage Eight: 24/25+ years old and lifelong

Why do we even bother to have age estimates? We notice by certain ages when there is a “hang up” – when maturation has halted in some capacity. That is why Autism can be diagnosed by the age of 2 or sometimes a bit earlier. It is because Autism specifically affects awareness, consistent limits, and warmth, and these in turn can pathologize further into distrust, inability to tolerate frustration, and estrangement. Similarly, an 8-year old struggling to be self-disciplined with acting appropriately in public shows signs of impulsivity more typical of an earlier age and may be a sign of failing to recognize authority figures or social norms and may be a sign of conduct disorder or oppositional-defiant disorder (ODD). There are many nuances to how disorders originate, but the point being made here is that the younger a child is, the less “pathological” the behavior will seem, all other things being equal.

At this point we can ask the following: where is the sensory-perceptual-cognitive faculty in the stages? Since stages one and two are pre-rational, awareness and trust would fall into this category at the same time as the “mind.” After reaching the “age or reason,” the biological, cognitive, etc. maturation still impacts psycho-spiritual but is not necessarily considered directly interrelated to truth, freedom, and care.

Below is a visualization of how the other developmental theories align with TFC Theory.

Below is an overview of how the person develops more generally across different capacities given the themes of what characterizes each stage.

REFERENCES

Aquinas, T. (1981). Summa theologica (Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Trans.). Christian Classics: Notre Dame, IN (Original work composed 1265-1273)

Aquinas, T. (1998). Commentary on the Gospel of St. John [Part II]. Translated by Weisheipl, J. A. & Larcher, F. R. Magi Books, Inc.: Albany, NY [Online version]. (Original work composed 1269-1272). Accessed via https://isidore.co/aquinas/SSJohn.htm

Aquinas, T. (2017). The Summa Theolgiæ of St. Thomas Aquinas [Second and Revised Edition]. Literally translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province (1920). Kevin Knight (2017). [Online Edition]. (Original work composed 1265-1273). Accessed via https://www.newadvent.org/summa/

Avallone, P. (1999). Keys to the Hearts of Youth. Salesiana Publishers, Inc: New York, NY

Azcarate, E. M. (1979). Maturation vs. Estrangement Growth Chart.

Azcárate, E. M. (2017). Building Truthful Relationships (self-published)

Azcárate, E. M. (2020). Draft of Maturation vs. Estrangement [on the first three stages]

Azcárate, E. M. & Hernandez, B. (1973). Youth Groups Off the Ground. Youth-Progressio [Christian Life Community magazine in Rome, Italy], 47(2) [March 1973], pgs. 13-20

Bernard (1153) On the Song of Songs. (Originally composed 1135-1153)

Bernard (2022). Following the Teacher and Master (from Bernard of Clairvaux: A Lover Teaching the Way of Love, 1997, New City Press: Hyde Park, NY). Magnificat, Vol. 24, No. 6 (August 2022)

Christian Prayer: The Liturgy of the Hours (1976). English translation prepared by the International Commission on English in the Liturgy. Catholic Book Publishing Corp.: New York, NY

Dubay, T. (2002). Prayer Primer: Igniting a Fire Within. Ignatius Press: San Francisco, CA

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY

Garrigou-Lagrange, R. (1989). The Three Ages of the Interior Life. Tan Books and Publishers: Rockford, IL (Originally published in French in 1938)

Groeschel, B. J. (2021). Spiritual Passages: The Psychology of Spiritual Development. The Crossroad Publishing Company: New York, NY. (Originally published 1983)

Harden, J. (1980) Modern Catholic Dictionary. Accessed via http://www.therealpresence.org/dictionary/adict.htm

Hoffman, M. L (2001). Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom

Ignatius of Loyola (2000). The spiritual exercises of St. Ignatius [Translated by L. J. Puhl (1951)]. Vintage Books (division of Random House, Inc.): New York, NY (Original work composed 1522-1524)

Martin, R. (2006). The Fulfillment of All Desire. Emmaus Road Publishing: Steubenville, OH.

Mowrer, O. H. (1964). The New Group Therapy. D. Van Nostrand Co.: New York, NY

Mowrer, O.H. (1970). Peer groups and medication: The best “therapy” for professionals and laymen alike. American Psychological Association Convention

Pinckaers, S. (1995). The Sources of Christian Ethics. The Catholic University of America: Washington, D.C. (Originally published in French, Les sources de la morale chrétienne, 1985)

Pope, C. (2013). On the Purgative, Illuminative, and Unitive Stages of Spiritual Life, as Seen in a Cartoon. Community in Mission [blog, November 8, 2013]. Archdiocese of Washington: Washington, D.C. Accessed via https://blog.adw.org/2013/11/on-the-purgative-illuminative-and-unitive-stages-of-spiritual-life-as-seen-in-a-cartoon/

Pope, C. (2016). The Stages of Sin from St. Bernard of Clairvaux – Fasten Your Seatbelts! Community in Mission [blog, September, 12, 2016]. Archdiocese of Washington: Washington, D.C. Accessed via https://blog.adw.org/2016/09/stages-sin-st-bernard-clairvaux-fasten-seatbelts/

Rist, J. (2009). The divided self: A classical perspective. In C. S. Titus (Ed.), The psychology of character and virtue (pp. 21-41). Arlington, VA: The Institute for the Psychological Sciences Press.

Schmitz, K. (2009). Person and psyche. The Institute for the Psychological Sciences Press: Arlington, VA

Seligman, M. E. P. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5-14

Shelton, C. M. (1983) Developmental Theory and Adolescent Spirituality: A Synthesis. Loyola Press: Chicago, IL

Skinner, B.F. (1971). Beyond Freedom & Dignity. Bantam Books / Vintage Books: New York, NY

Skinner, B.F. (1974). About Behaviorism. Vintage Books: New York, NY

Valle, A., Cabanach, R. G., Núñez, González-Pienda, J., Rodríguez, S., & Piñiero, I. (2003). Cognitive, motivational, and volitional dimensions of learning: An empirical test of a hypothetical model. Research in Higher Education, 44(5), 557-580 (October 2003)

Vitz, P., Nordling, W. J., & Titus, C. S. (2020). A Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person: Integration with Psychology & Mental Health Practice. Divine Mercy University Press: Sterling, VA

Notably, an alternate translation is given in the footnote of the New American Bible - Revised Edition: “May the God of peace himself make you perfectly holy and sanctify your spirit fully, may both soul and body be preserved blameless for the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.” This alternate translation emphasizes, through separation of the terms, that the soul and body are the “natural” parts while the spirit is “supernatural.” This is further evidenced by those who argue how animals have souls (“psyche”) but do not have spirits (“pneuma”).

Pneuma is the Greek translation of the Hebrew word ruah (רוּחַ), or the life-breath that God breathed into Adam

see Garrigou-Lagrange (1938); Harden (1980); Groeschel (1983/2021); Martin (2006); Pope (2013)

Indirectly referencing Hoffman (2001) with whom we would agree there needs to be an integration of empathic affectivity (i.e., involuntary emotion for another’s suffering) and empathic cognition (i.e., perspective taking)

Prudential personalism, in part, is an attempt to reconcile natural law (objective truth) with the personalist norm (phenomenological approach, subjectivity, conscience, etc.)

referencing Jn 14:6, this is a Scriptural example that Azcárate commonly uses to explain the centrality of Jesus as our Truth, Freedom, and Care. St. Bernard of Clairvaux provides a similar reflection on this same verse by commenting on Jesus is the “Way” because He is our “example of humility” and “model of meekness” (basis for our willed actions), the “Truth” because He is “the light of life … that enlightens every person”, and the “Life” because He is “food, the viaticum, to sustain you on your journey” (alluding to loving union) (Bernard, 1997/2022, pgs. 302-303). St. Thomas Aquinas also reflects on this passage and regards “the life” as referring to one of man’s greatest desires which is to “continue to exist,” which corresponds to our premise that the heart includes that drive for self-preservation found in our personal unity (unum) (Aquinas, 1272/1998, Ch.14, lect. 2, #1868).

Skinner (1974) pg. 217, i.e., freedom is a feeling of being free insofar as we are not tending to “escape or counterattack” something; also see Skinner (1971), Ch. 2

Beatriz began “Cool Clean Christians” for the girls of St. Anthony of Padua Parish in Falls Church, VA around 1973 and Eduardo and Beatriz began Catholic Life Community (partly modeled after Christian Life Communities) for the boys and girls, respectively, in 1974.

see Aquinas (1273 / 1981), II-II, 24.9; also, Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 519

Also, see pg. 290 for more description of moral and spiritual evil and pgs. 292-293 for section on “Vices”

referencing Bernard of Clairvaux (1153), Sermon 63.6b

Interestingly, Mowrer read some of the writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas, which he regarded as an “earlier and more remarkable anticipation of the fruits of latter-day, psychological research and scholarship.” (Mowrer, 1964, pg. 104)

Referencing Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi (2000)

Loosely defined according to Rokeach’s terminology, Stages 5, 6, 7, 8 are terminal values (end-states) that all affect one another and even cause one another. Stages 1-4 are instrumental values (behavioral repertoires that lead to subsequent instrumental values and ultimately to terminal values; though one could argue that Stages 1-4 are also end-states). However, there is much overlap and this distinction is not the most important one to make with perhaps the exception of Stages 5 and 8 being understood as solely end-states for which we are continuously pursuing.

In this example, one could also see that there is not a fullness of the truth due to the person failing to see the truth of the dignity of the other person.