Philosophical Premises of TFC Theory - The Transcendentals

Written by Joseph Clem, M.Ed.

This article does not constitute professional advice or services. All opinions and commentary of the author are his own and are not endorsed by any governing bodies, licensing or certifying boards, companies, or any third-party.

“Through him the whole structure is held together and grows into a temple sacred in the Lord; in him you also are being built together into a dwelling place of God in the Spirit.”

— Eph 2:21-22

In His Image and Likeness

“You formed my inmost being; you knit me in my mother’s womb. I praise you, because I am wonderfully made; wonderful are your works! My very self you know” (Ps 139:14). These words from King David seem to be a good place to begin a discussion on human development. Before we develop, we are created. If we forget this, then we decontextualize human development from our origin, our purpose, and our destination. When we remember Who we come from, to Whom we belong, and to Whom we are going, then we develop into the fullness of who we are meant to be.

Theories about how we operate as souls and how we mentally grow predates Christianity. King David has already been quoted as he praises God in wonder for having been made. Centuries go by and some of the first philosophers, Plato and his student Aristotle, began to theorize how we mentally process as either the brain or heart, respectively. For a few hundred years, there in Greece and in other places of the world, human beings wrestled with the mystery of how they operate and mature mentally.

Then in the 1st century, Jesus Christ, God Himself, came to be like us in human development as He “advanced in wisdom and age and favor before God and man” (Lk 2:52). He taught us healthy human development through the love of the Holy Family, through community-building, through authenticity, through human touch and tenderness, through doing the Will of God for the sake of love, and through every perfection of what we ought to do and become as humans.

If we are made in the image and likeness of God, Jesus is central to understanding ourselves because He is God taking on our likeness. He teaches us how to develop better than anyone. It is as if the author of a book entered into the story to help guide the characters through a conflict toward a happy ending. Would we not be wise to listen to the voice of the Author? Jesus reveals a radical, divine love that is coming after us – it is seeking us out by name over and over again. The Author of the book, in which we are created to be protagonists, wants to lift us up beyond the “earthly book reality” into a “more real reality” where the Author exists both outside the story and inside the depths of the story. For what reason? Communion. As Isaiah prophesied, “your Builder shall marry you” (Is 62:5). We are made for self-gift and receptivity with one another and, even more remarkably, with our Creator. We are made for love between persons of our own nature and, beyond our comprehension, with the Supernatural Persons of the Trinity. As will be explored, Jesus is our Love, Truth, and Freedom incarnate as we strive for mutual indwelling with Him. Likewise, the other Persons of the Trinity point to these ultimate, objective values.

Why does God love us? We are beautiful. Why are we beautiful? Because He is Beauty — we have been made to resemble, configure, and unite ourselves to Him Who alone makes us lovable. “To be sure, God has left traces of his Trinitarian being in his work of creation …” (CCC #237) and we are the masterpiece of His creation. We are truly good and beautiful, made to be whole and in relationship with God, others, and even ourselves. In that statement is the woven texture of being with its essential properties – truth, goodness, beauty, unity, and relationality – the transcendentals (see Schmitz, 2007).

The Transcendentals and Natural Inclinations

From Jesus to now, all philosophers, theorists, and scientists have sought, knowingly or not, to unfold the mystery of who we are in the light of Christ. Particular beacons throughout history are available to us, namely the Saints. Many, such as St. Augustine of Hippo, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Ignatius of Loyola, and more recently St. John Paul II have each in their own way contributed to our understanding of the human soul and how we develop spiritually, emotionally, intellectually, and relationally. Each of these capacities of the soul have an underlying ideal to which they are oriented. Most recently, the Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person (CCMMP) re-articulated that our most basic, natural tendencies are based in the transcendentals of “unity (unum), truth (verum), goodness (bonum), relationality (aliquid), and beauty (pulchrum)” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 261 and see pg. 384; Schmitz, 2007 & 2009; Saward, 1992/2008 regarding St. Bonaventure’s pivotal role in promoting beauty as a transcendental).1 More than natural tendencies, the transcendentals are essential properties of a being.

… within the mixture of being, and non-being that constitutes reality, as distinct from the texture of being, in the mix of light and shadow, of benefit and privation, we find the remote foundations of the virtues in the texture of being and its transcendental properties. For within the inclinations of our nature, there is embedded the promise of the future realization of our essential humanity (essentia, res humana), the guarantee of our individuality, our oneness of being (unum), and the hope of genuine community in our relationality (peaceful and productive co-existence, aliquid); in the honesty (verum) with which we probe the meaning of things (their intelligibility), and face the trials and disappointments of our adversity, as well as the joy of understanding one another and the world we encounter, finding in it a deeply seated good (bonum) in being alive, in concert with others, in an environing world; able to appreciate it’s astonishing beauty (pulchrum). All of these transcendental properties of being provide the ground for the development of our humanity. It is our responsibility to recognize the texture of being as well as the mix of reality within which it is ensconced, using the transcendental properties of being as the ground for the development of virtue and maturity.”

— Schmitz, 2009, pg. 50

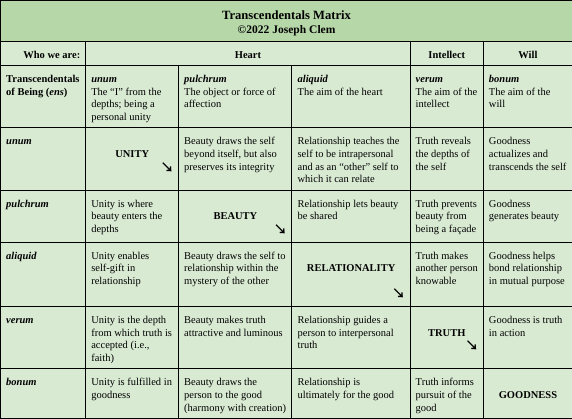

Below this line is content for paid subscribers and includes descriptions of the transcendentals and how they relate to one another. Also included is a matrix chart to visualize how these transcendentals inform one another while culminating in the good.

Why do the transcendentals matter in regards to TFC theory? There are multiple reasons, but first and foremost we must know what the properties of being are before we discuss the development of being. “What we have been given in our constitution is much, for it is the very compass of human development towards maturity that comes to us, and the texture of our being, and the specific inclinations of our nature” (Schmitz, 2009, pg. 31). The transcendentals and their accompanying natural inclinations provide meaning and direction to our growth.

… what philosophers call ‘natural law’ is not a negative and external set of prohibitive rules, but the invitation to participate freely, positively, and intimately in the existential power of the transcendental properties of being, of unity, relationality, the true, and the good, and — if one is sensitive, aesthetically and artistically — of beauty … a sort of material and formal a priori that inclines (but does not compel) a human agent to act in certain ways.

— Schmitz (2009), pgs. 79, 80

Here, we are speaking of inclination, not determination. It is the natural inclination of free will toward the good. All transcendentals culminate in the good. Together, they give us a “natural law” that is “ the pre-rational orientation inborn in the human agent, and his or her nature— an orientation that is intended to be taken up into an intellectual and spiritual dimension, and integrated within the conditional and voluntary dynamism of the human person.” (pgs. 80-81). I would add affective in addition to the cognitional and voluntary within our interior dynamism.

Below I offer definitions of each from an ontological and an experiential level:

Unity: every being is one united existence and essence (united in its actuating presence and in its formal structure, substance, identity, character, etc.)2 as opposed to merely being part of one substance (pantheism); every being is drawn toward self-preservation as a personal unity – a singular whole, proper to itself

Beauty: every being is beautiful — an object of affection and “that which instinctively appeals” (Harden, 1980) (i.e., God delights in us for our simple existence) as opposed to the belief that every being is fundamentally ugly (an object of displeasure, or repulsion); every being is ordered toward integrity, harmony, luminosity, and mystery

Relationality: every being exists in and is ordered toward relationship with other beings as opposed to a complete opposite belief that the self is the only being that exists (solipsism); every being itself is an “other” to which other beings are oriented (e.g., every person is in someone else’s orbit) as opposed to the belief that only other beings are orbital while the self is the center (as in narcissism)

Truth: every being is true — a reality that is intelligible and cannot be denied as opposed to living a fantasy in rebellion against or in ignorance of reality; every being is also ordered toward truth (reality) in which it exists

Goodness: every being is good (proper and fitting to creation as it ought to be) and oriented toward goodness (whatever is proper and fitting) as opposed to the belief that beings are fundamentally evil (i.e., deficient in part or whole, or inherently disordered) as is found in some Christian heresies; “whatever is suitable or befitting someone or something” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020) and what underlies all other transcendentals

At first glance, we might wonder about “unity” which is the inclination to continue our existence in bodily and spiritual health and integrity. How do we explain virtuous self-sacrifice (relationality) in light of the natural inclination for unity? God, Who is One, is also Three. Although it is not a perfect analogy, we echo in some way this Divine Mystery by giving part of ourselves. “People override this natural inclination [of personal unity] in order to make intentional sacrifices for the sake of a higher inclination to family, society, and religion” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 265). One example of this in practicality is a Eucharistic spirituality, as is practiced within my community of Youth Apostles, in being “taken, blessed, broken, and shared with others.” We strive to forgo personal needs in order to serve the higher goods, and this is in imitation of Jesus Who gives the entirety of Himself in the Eucharist and in imitation of Mary’s radical “yes.” However, one could argue that we retain personal unity as we transcend to union with Christ and thus enter into the mystery of the Unity and Trinity of God. We are challenged to ponder how individualistic cultures remain stuck in the desire for continued existence, or for only beauty, or for only relationality, all disintegrated from one another and divorced from truth and goodness. The transcendentals must all coexist to be fully realized in the self and in relationships.

The CCMMP posits that we experience a cycle of desiring (1) personal unity, (2) family relationship, (3) truth in general and truth of God, (4) societal relationship, and (5) beauty, and that the underpinning basis for all of these is the desire for goodness (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 262, Fig. 11.1, referencing Aquinas, 1273/1981, I-II, 94.2; Ashley, 2006; Schmitz, 2007 & 2009).3 What I am proposing is not a contradiction, but rather an added perspective that tries to answer the question: how do each of the transcendentals relate to one another? Each of the transcendentals, in some way, reflects one another because they are all descriptions of God Who is One Unity (Unum), Beauty (Pulchrum), Trinitarian Relationship (Aliquid), Truth (Verum), and Goodness (Bonum). Therefore, I believe that when we speak of one transcendental, we necessarily refer to all of them. This is in order to understand ourselves and God with a more integrated perspective and, subsequently, to live a more integrated life. I also attempt to reconcile this with the understanding of how the other transcendentals orient toward goodness in terms of the order of our experiences, processing, and responding from a psychological perspective. I believe the answer is in how goodness is the fulfillment of our volitional capacity, (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 420; i.e., the human tendency toward the good is manifest in different volitional inclinations.”) and our will is the culminating, unveiling act following the heart and the mind. All transcendentals lead to goodness, “the principle of finality (bonum)” (Schmitz, 2009, pg. 19). “An interior knowledge of goodness gets to the heart of reality, for goodness is the right ordering of our lives. Our emotions are conformed to our will, our will to our reason, and the whole person is subject to God” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 503). Even Dietrich von Hildebrand, the “philosopher of beauty,” regarded the good as the most important transcendental of the spiritual life among truth, beauty, and goodness. Schmitz makes the argument by naming moral values as the most important, among other values (i.e., aesthetic, intellectual, etc.), which “most directly form us in the completion and maturity of our humanity, for these alone determine the value of the exercise of responsible freedom” (Schmitz, 2009, pg. 49).4 To paraphrase Bishop Robert Baron, lacking certain truths or lacking appreciation for certain beauties are not necessarily catastrophic for the spiritual life, but lacking the good in the moral life is “spiritually ruinous.” (Barron, 2022). However, as will be explored further: “The human ideal is volitive action grounded in affective response and cognitive reflection. (Russell, 2009, pg. 169)

Also, my perspective proposes how we can frame this within the understanding of our affective, rational, and volitional capacities. Below is an attempt to show examples of how each of the transcendentals relate to one another within the traditional powers (affective, cognitive, and volitional) of the person — heart, intellect, and will. Heart (fulfilled by existence and personal unity, beauty, and relationality in love) and mind (fulfilled by truth) lead to the will (fulfilled by freedom for goodness). This will also help ground the theology of the person to be discussed later.

The transcendentals need one another. Without an integration of them, unity becomes self-hatred, beauty becomes ugliness, relationality becomes selfishness, truth becomes lies, and goodness becomes evil.

The unity of a thing may suffer disintegration (character); the relationality of things may be destructive (conflict); the intelligibility of things be distorted and darkened (illusion); the desirability of things conflicted (negation); and so, too, with beauty and its luminosity. Just as disunity disrupts the unity of being, error its intelligibility, evil its goodness, so too the ugly may mar the face of being.

— Schmitz (2009), pg. 13

It is also important to note that at our most innate level, we have these universal properties of being, even if they become distorted as a consequence of original sin.

For example, they [natural inclinations] are subject to developmental disorders (caused by biological deformation, trauma, and lack of secure attachment), neurocognitive disorders (caused by deficits in decision making and error-correction capacities), and moral distortions (caused by evil choices, narcissism, hatred, acting out of fear, and lack of forgiveness).

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 421

The opposites of the transcendentals (i.e., ugliness, lies, evil, etc.) are not essential properties of being and therefore not at the same level of existence. In fact, they do not exist as “things.” Evil is actually the absence or distortion of what is inherently good. Even the first sin was committed by “focusing on the fruit as good to eat, beautiful, and a source of wisdom [truth]” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg., 506, emphasis added). Regarding distortion and privations of transcendentals at an experiential level (as distinct from the metaphysical level which is unchanging):

“The texture of being may well offer us the true and the good, but the mixture of reality also offers us dark shadows and thieves that masquerade in the garb of those very transcendental properties. Indeed, the finite order in which we live presents the transcendental values in limited versions, and in conditions in which they may be more apparent than real or even come into seeming conflict with one another. Moreover, in their finite embodiment, they are subject to deprivation, through injury or corruption, as in the cataclysms of nature, which might serve nature well but humanity poorly. Even more privative is the special deviance that arises out of the misuse of our liberty and distracts us from the inclinations pre-given in our nature, inclinations that are no longer processes but directive actions taken up into agency.”

— Schmitz, 2009, pgs. 77-78

Through the transcendentals, we are looking for God. “This search for God demands of man every effort of intellect, a sound will, an ‘upright heart,’ as well as the witness of others who teach him to seek God” (CCC #30). We are seeking truth, freedom, and love because He is Truth, Goodness, and Beauty and Love (CCC #33, 41). “We are head, hands, and heart. We respond to truth, goodness and beauty. We are this because we are images of God. Each of us is one person with three distinct powers” (Kreeft, 2008/2015; also see Kreeft, 2020, pgs. 43-65, i.e., (pg. 54) “For God is not just reason and will but also heart.”). As the arrows show in the Transcendentals Matrix, the powers culminate in actions for the good, the purpose of our freedom.

We hear more often the following: God is Beauty. God is Love. God is Truth. God is Goodness. If we are made by God and for God, then it follows that we are made for whatever is true, good, and beautiful, and that we are made for love. Besides the titles of God, love and beauty are also philosophically connected in an explanation of Thomistic philosophy5 and Hildebrandian philosophy (i.e., love is responding to the objective beauty of the person). Divine Love is Divine Relationality (Aliquid) since relationality in God is Interpersonal Love Itself — the Trinity.

The heart is personal unity (intrapersonal encounter), body-spirit affect and desire (thirst for beauty), and relationality (interpersonal encounter).

Unity of the Heart

Why is unity assigned to the heart rather than to the intellect (i.e., unifying the heart to the will mediated through reason) or to the will (i.e., unifying the heart and intellect in a culminating act), which are not necessarily incorrect views either? It is because the heart itself is also defined as our deepest self, our truest self, our centrality and our personal unity beyond affection, reason, and volition, hence why the heart cannot be limited to affect. St. John Paul II shares the following:

Eastern [Catholic] spirituality makes a specific contribution to authentic knowledge of man by insisting on the perspective of the “heart.” Christians of the East love to distinguish three types of knowledge. The first is limited to man in his bio-psychic structure. The second remains in the realm of moral life. The highest degree of self-knowledge is obtained, however, in “contemplation,” by which man returns deeply into himself, recognizes himself as the divine image and, purifying himself of sin, meets the living God to the point of becoming “divine” himself by the gift of grace. This is knowledge of the heart. Here, the “heart” means much more than a human faculty, such as affectivity, for example. It is rather the principle of personal unity, a sort of “interior space” in which the person recollects his whole self so as to live in the knowledge and love of the Lord. Eastern authors are referring to this principle when they invite us to “come down from the head to the heart.” It is not enough to know things, to think about them; they must become life.

— John Paul II (1996)

Beyond this Angelus reflection from St. John Paul II, Scripture and the Catechism define the heart as the deepest self. Some might say the will is the true self, or that the will is synonymous with the heart. I would say our will is our truest self in the moral sense (i.e., having the final word), but our heart is the truest self in the realm of love (genuine delight in the beauty and personal being of the beloved) and of being (the personal unity) ontologically.

From this understanding of the heart, we can take the perspective of how the “unity” of the Father and the Son is the Holy Spirit (Newsome, 2022, e.g., “the heart of the Trinity”). The Holy Spirit is Divine Unum, Divine Pulchrum, and Divine Aliquid, as is shown in how the Holy Trinity is the foundation for the theology of the person (see the next section). Yet the Holy Spirit, in His own Person, is also the Spirit of Truth (Jn 14:17; Jn 15:26; Jn 16:13; John Paul II, 1993, #83), the Spirit of Freedom (2 Cor 3:17; John Paul II, 1993, #83), and the Spirit of Love (Rm 15:30; Gal 5:22; Aquinas, 1273/2017, 1a, 37.1; John Paul II, 1993, #83). Likewise, each Person of the Trinity is the fullness of Truth, Freedom, and Love. In the theology of the person, we call Jesus the “Art of the Almighty” or the Beauty of “Father-Artist” (Saward, 1992/2008, referencing St. Bonaventure and St. Augustine), but isn’t beauty proper to the heart which we have identified as the Holy Spirit in the Trinity? In relation to Each Other, They are equal Beauty. This is part of the mystery of the Trinity. It is within this Mystery that we can see “the ultimate foundation of interpersonal relationships is the Triune God, who is a unity (one God) in a community of love (three divine Persons)” (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pgs. 317-318). Each Person of the Trinity represents these transcendentals because the Persons are a Unity; however, “the unity of the three divine Persons with each other is greater and stronger … in Trinitarianism than the unity of a single divine Person with himself in Unitarianism because love is a greater and stronger unity” (Kreeft, 2020, pg. 57).

Here is another note on how our heart is defined as an internal unity from Kreeft:

When we search for the heart, if we go deep enough, we delve down beneath feelings and even beneath the conscious will and we come upon the mystery of the self, the “I,” the personal subject that has all our powers and does all our acts that are aimed at any object, mental or physical. This non-objectifiable subject cannot be an object, and therefore cannot be an object of consciousness. We can know of it, we can know that it exists, but we cannot know it as we know the objects of our consciousness.

— Kreeft, 2020, pg. 141

Yet, we are still called to love ourselves so that we can truly love our neighbor as ourselves. We need to encounter, accept, and love the “I” at the center of our being which has its being through Love Itself. Self-denial is not the same as self-hatred or self-disintegration. We cannot destroy ourselves in the process of being a gift. In a critique of our times, Kreeft observes: “We are not at one and at peace even with ourselves. We divide our “I” by multiplying our “its.” We identify with so many things that our “I” loses its unity. And whatever loses its unity, loses its being, its life” (Kreeft, 2020, pg. 211). We are called to wholeness so that we can be a whole gift.

Relationality of the Heart

“beings, however, are not closed off from one another …”

— Kenneth Schmitz , 2009, pg. 12

In regards to relationality (aliquid), which is a philosophical term that we may substitute for interpersonal relationships6 in the context of psycho-spiritual operations, why is this assigned to the heart? This may be especially perplexing since interpersonal relations and love necessarily integrate all the powers — the heart (affection for the other), the intellect (knowing the other), and the will (acting in sacrificial love for the other). However, we characterize it according to the heart for the purposes of understanding Azcárate’s psycho-spiritual development which organizes interpersonal and intrapersonal affection according to its own domain.

This domain of interpersonal and intrapersonal affection is distinct, yet integrated, with the will and the intellect as the other two domains, which is also consistent with Hildebrandian philosophy. It will be stated multiple times that the heart is much more than emotions, as well. In the same way that the Holy Spirit is Divine Relationality, and Divine Relationality is the Holy Trinity as a whole, so also the heart is the place of love, and yet love integrates the heart, intellect, and will — such is the mystery of ourselves. Love is so simple and so complex as to deserve our full attention. Genuine and full love is all at once knowing the beloved with the intellect, choosing the good of the beloved with the will, and consenting to tender affection toward the beloved with the heart. The Thomistic will-based (volition) emphasis and Hildebrandian heart-based (affection) emphasis are two different focal points of the same, integrated love. The intellect ensures that the will and the heart do not become divorced from one another for the intellect observes and mediates between the two. Like a three-note chord (i.e., 1st, 3rd, and 5th interval of an octave) played on strings or like using a three-finger grip (index, middle, and thumb) on a pen to write, the soul requires the three-power collaboration (rational, volitional, and affective) to operate as a fully alive and integrated human person. Yet relationality is assigned to the heart because it is the same faculty by which we encounter our own selves and by which we encounter God in prayer.

What is the order of the transcendentals in the heart? We know from Aquinas that after defining a thing (res) and then a being (ens), we define unity (unum) which precedes truth and goodness. Where are beauty and relationality if we are to adopt the list from the CCMMP which also draws heavily from Aquinas? We clearly cannot define relationality (aliquid) until after we define the personal unity (unum) of the self. A moon does not orbit a planet (drawn to its gravitational force — extrinsic center of gravity) until the moon itself has its own integrity and individuality (its matter being pulled inward by its core — intrinsic center of gravity). Otherwise the moon will fall apart from implosion (lack of extrinsic gravity or relationality) or explosion (lack of intrinsic gravity or personal unity). In a similar way, we have a heart that has an intrinsic and extrinsic “spiritual gravity” that keeps us in orbit.7 The heart is the “I” in personal integrity and wholeness, and it is the “I” in relation to others. Below is an attempt to logically explain how unum is related to aliquid, and I believe a similar logical explanation can be made of the relation between each transcendental:

Unity (unum) is the drive for continued, personal existence

Relationship (aliquid) with God is originative, necessary, and the purpose for existence

Relationship with other persons is derivative of our drive for relationship with God

Therefore unum needs aliquid

Also …

Aliquid is the drive for relationship

Relationship requires whole, unique, individual, and singular persons

Wholeness and personal unity requires unum

Therefore, aliquid needs unum

Aliquid is an essential property of being because the self is also an “other” in relation to other selves. We are beings in others’ orbits. Most fundamentally, we are relational to God as infinitely “other” (aliquid) than Him because He is infinite and existence Itself.

Beauty of the Heart

In regards to beauty, it helps to look at Aquinas’ definition as integrity, harmony (or proportionality), and clarity (or luminosity) in order to contextualize it among the transcendentals.8 Does beauty precede or follow relationality? I believe beauty precedes relationality. What would necessarily attract us to the other, who is essentially beautiful, unless we had an initial, innate desire for integrity, harmony, and clarity – the beautiful?

Beauty, luminosity, harmony, and integrity are qualities of all that exists, even when these qualities are hidden from direct view. A person can thirst for beauty just as he thirsts for life itself. Beauty is found in the goodness of all that exists, in all that is true, in all that is good in interpersonal relationships.

— Vitz, Nordling, & Titus (2020), pg. 399

Therefore, the order in the Transcendental Matrix© and the Theology of the Person© is Unity, Beauty, Relationality, Truth, and Goodness. Pope Benedict XVI shares the following regarding what he called “a via pulchritudinis, a path of beauty”:

An essential function of genuine beauty, as emphasized by Plato, is that it gives man a healthy “shock,” it draws him out of himself, wrenches him away from resignation and from being content with the humdrum – it even makes him suffer, piercing him like a dart, but in so doing it “reawakens” him, opening afresh the eyes of his heart and mind, giving him wings, carrying him aloft.

Authentic beauty … unlocks the yearning of the human heart, the profound desire to know, to love, to go towards the Other, to reach for the Beyond. If we acknowledge that beauty touches us intimately, that it wounds us, that it opens our eyes, then we rediscover the joy of seeing, of being able to grasp the profound meaning of our existence, the Mystery of which we are part; from this Mystery we can draw fullness, happiness, the passion to engage with every day.

Beauty, whether that of the natural universe or that expressed in art, precisely because it opens up and broadens the horizons of human awareness, pointing us beyond ourselves, bringing us face to face with the abyss of Infinity, can become a path towards the transcendent, towards the ultimate Mystery, towards God.

— Benedict XVI (2009), emphasis added9

If Beauty “pierces” then let us consider an arrow that aims at the heart with beauty as the arrowhead, truth as the wooden length of the arrow providing structure, and goodness as the fletching feathers that help orient the arrow in the correct direction. Notice that this is one (unum) arrow and when it is not aimed at our own heart it is aimed at an “other” (aliquid). The immediate effect of beauty is desire and the subsequent effect of aliquid is described beautifully by Pope Benedict XVI and is worth repeating: “it draws him out of himself … giving him wings, carrying him aloft … to go towards the Other … pointing us beyond ourselves.”

I would add one more feature of beauty to Aquinas’ list of beauty’s features – beauty is mysterious, partly inspired by Benedict XVI’s address to artists, in which he refers to God several times as “Mystery.” We are drawn not only to things that are clear to us, as in luminosity, but also the mysterious, wild, unpredictable, unexplainable, and foreign, though it cannot be contrary to the other qualities of beauty. The heart delights in appreciating something that is beyond the comprehension of the mind. Admittedly, one could argue that “mystery” is a descriptor of aliquid, rather than pulchrum, but I hold that mysteriousness is a descriptor of both. Perhaps some might even argue that mystery is proper to the intellect since it is a search for knowledge. However, there is a search for beauty which is less tangible in “knowing” and is rather an affective response. There is also a search for the mystery of persons, even the self. The mind can respond rationally to a mystery, but only the heart can respond affectively as a value-response to something that is valuable and beautiful beyond what reason can articulate. We find the fullness of mystery as a necessity of beauty in the ineffable Beauty of God Who draws us to Himself – to His Mystery, which is why His Beauty is ineffable, indescribable, and unattainable via the intellect or will. We can only encounter His Being as Beauty through the heart which value-responds to His Supreme Value and Mystery.

There is something intriguing about another “self” that is different from your “self.” There is something “awe-ing” about the wildness of nature (Donaghy, 2022). There is something transcendental when pondering and wondering about the mysteries of faith. They are beautiful in that they keep the upward impulse of eros-agape alive – our motivation and passion and heart remain alive through the mystery of beauty and Beauty. Beauty is a necessary transcendental and it specifically relates to love.10 St. Augustine confesses:

Do we love anything save what is beautiful? What then is beautiful? And what is beauty? What is it that allures us and delights us in the things we love? Unless there were grace and beauty in them they could not possibly draw us to them.

— Augustine (401/2017), IV.XIII, pg. 77

Dietrich von Hildebrand, likewise, provides examples of how beauty can be ineffable or indescribable whether in awe toward nature, art, and music, or in the delight toward something or someone of objective value. We cannot describe why we are touched (or cut) to the heart, only that we are affected, because “the heart has its reasons which reason knows not” (Pascal, 1660, pt. 2, art. 17, no. 5).

Thus we have a synthesized “way of beauty” (pulchrum) that begins with integrity (wholeness) of personal unity (unum); next being drawn into the mystery of the other (aliquid); then seeking clarity in the truth (verum); and finally entering into harmony (order and proportionality) with existence in goodness (bonum).

The Way of Truth and the Way of Goodness

Just as there is a “way of beauty” (via pulchritudinis) meant to primarily penetrate the heart, I posit that there is a “way of truth” (via veritatis) meant to primarily penetrate the intellect and that there is a “way of goodness” (via bonitatis) meant to primarily penetrate the will. However, all of these “ways” should ultimately penetrate the person’s entire being in heart, intellect, and will. Truth, goodness, and beauty are inseparable, yet each is a gate to the same city, a river to the same ocean, and a branch to the same tree. These “ways” are of practical import when considering the best way to evangelize.

The way of truth focuses on evoking use of a person’s reason. This is an invitation to draw a person’s mind to reality. When the intellect sees truth, it experiences peace which makes the will and the heart desire meaning and happiness.

The way of goodness focuses on evoking use of a person’s will. This is an invitation to act in accord with goodness. When a person acts in freedom toward the good, the will finds its purpose. When the will experiences this meaning, the intellect becomes open and the heart becomes softened so that both are more receptive to the truth and to objective beauty.

Although personal unity and relationality align with the heart as akin to affection for the beautiful, the intrapersonal and interpersonal affection encompass all three ways of evangelizing. It might be said that the personal journey in the context of relationship must involve the ways of beauty, truth, and goodness in order for the person to be properly evangelized.

Do you call with all voices which to You are one? Is not the difference of Your voices to be found in me and not in You who are absolutely One, and yet the source of all multiplicity and variety? Do You, who are all truth and goodness and beauty, use all things which are passing in their variety and multiplicity to call me?

— Groeschel (1983/2021), pg. 190

The multiplicity of how God and others reach us and how we reach others points to how we are made universally in our humanity and particularly in our personhood.

REFERENCES

Aertsen, J. A. (1991). Beauty in the Middle Ages: A Forgotten Transcendental? Medieval Philosophy & Theology, Vol. 1, pgs. 68-97 https://doi.org/10.5840/medievalpt199115 (Originally presented as the Cardinal Mercier lecture at the Catholic University of Louvain on 22 February 1990)

Aquinas, T. (1920). The Summa Theolgiæ of St. Thomas Aquinas [Second and Revised Edition]. Literally translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Kevin Knight (2017). [Online Edition]. (Original work composed 1265-1273). Accessed via https://www.newadvent.org/summa/

Aquinas, T. (1954). De Veritate [HTML Edition by Joseph Kenny, O.P.; translated from the definitive Leonine text by Robert W. Mulligan, S.J. (Q1-9), by James V. McGlynn, S.J. (Q10-20), & by Robert W. Schmidt, S.J. (Q21-29). Henry Regnery Company. (Original work composed 1256-1259). Accessed via https://isidore.co/aquinas/english/QDdeVer.htm

Aquinas, T. (1981). Summa theologica (Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Trans.). Christian Classics: Notre Dame, IN (Original work composed 1265-1273)

Ashley, B. M. (2006). The way toward wisdom: An interdisciplinary and intercultural introduction to metaphysics. University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, IN

Augustine (2017). Confessions. Translation by F. J. Sheed (1942/1943). Word on Fire Catholic Ministries: Park Ridge, IL (Original work composed 397-401)

Barron, R. (2022). Seeking the Good and the Beautiful. Word on Fire. Published July 25, 2022. Originally presented at the Albert Cardinal Meyer Lecture series hosted at Mundelein Seminary in March 2022. https://www.wordonfire.org/videos/wordonfire-show/episode344/

Benedict XVI (2009). Meeting with Artists [Address of His Holiness in the Sistine Chapel on November 21, 2009]. Vatican City, Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana

CCC = Catechism of the Catholic Church (2012). Vatican City, Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Donaghy, B. (2022). LOTR, Family Life, and Ring-Tailed Lemurs w/ Bill Donaghy [with Matt Fradd] . Pints with Aquinas [podcast]. Published August 12, 2022

Groeschel, B. J. (2021). Spiritual Passages: The Psychology of Spiritual Development. The Crossroad Publishing Company: New York, NY. (Originally published 1983)

Harden, J. (1980) Modern Catholic Dictionary. Accessed via http://www.therealpresence.org/dictionary/adict.htm

John Paul II (1993). Veritatis splendor [Encyclical, on certain fundamental questions of the Church’s moral teaching]. Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, Vatican

John Paul II (1996). Eastern Spirituality Emphasizes the Heart [Angelus Reflection, September 29, 1996]. L’Osservatore Romano - Weekly Edition in English. The Cathedral Foundation: Baltimore, MD. Accessed via https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/eastern-spirituality-emphasizes-the-heart-8819 on March 3, 2023.

Kreeft, P. J. (2015). Truth, Good, and Beauty - the Three Transcendentals. Living Bulwark [online publication]. Vol. 81, August/September 2015 (Originally published in 2008 as an essay “Lewis’ Philosophy of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty” in Baggett, Habermas, Walls, & Morris (2008). C.S. Lewis as Philosopher: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty). Accessed via https://www.swordofthespirit.net/bulwark/august2015p23.htm on August 4, 2022

Kreeft, P. J. (2020). Wisdom of the Heart: The Good, True, and the Beautiful at the Center of Us All. TAN Books: Gastonia, NC

Newsome, M. (2022). The Holy Spirit: The Heart of the Trinity. Test Everything Blog. Homily for Pentecost, June 5, 2022. Accessed via https://testeverythingblog.com/the-holy-spirit-the-heart-of-the-trinity-34745abbad0a on August 12, 2022

Pascal, B. (1660). Pensées

Russell, H.A. (2009). The Heart of Rahner: The Theological Implications of Andrew Tallon’s Theory of Triune Consciousness. Marquette University Press: Milwaukee, WI

Saward, J. (2008). The flesh flowers again: St. Bonaventure and the aesthetics of the resurrection. The Downside Review (in association with Downside Abbey), Vol. 110 (378). Accessed via http://www.christendom-awake.org/pages/jsaward/fleshflowers.htm on August 12, 2022. (Originally published 1992)

Schindler, D. C. (2017). Love and Beauty: The “Forgotten Transcendental” in Thomas Aquinas. Communio 44 (Summer 2017). Communio: International Catholic Review (Originally delivered November 3, 2016)

Schmitz, K. (2007). The texture of being: Essays in first philosophy. The Catholic University of America Press: Washington, D.C.

Schmitz, K. (2009). Person and psyche. The Institute for the Psychological Sciences Press: Arlington, VA

Vitz, P., Nordling, W. J., & Titus, C. S. (2020). A Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person: Integration with Psychology & Mental Health Practice. Divine Mercy University Press: Sterling, VA

note that aliquid technically refers to “something” (see Aquinas, 1259/1954, Q1, Art. I, Respondio, e.g., “the distinction of one being from another, and this distinctness is expressed by the word something, which implies, as it were, some other thing. For, just as a being is said to be one in so far as it without division in itself, so it is said to be something in so far as it is divided from others.”) but functionally this means that a being can be one among many (divided or shared) with others, hence why the CCMMP calls this “relationality” and why we will refer to this with the same term, as well

According to Schmitz (2009), unity (unum) understood ontologically “consists precisely in the communion of existence and essence that constitutes it as an individual being, the union of existential energy and formal structure” (pg. 11). Note that Schmitz dives deeper into the ontology of the person by stating that unum is the third transcendental after ens (being) and res (thing) (see pgs. 9-11), but ens and res are not major focal points of defending Azcárate’s theory of psycho-spiritual development. One might argue that the natural inclination toward self-preservation is aligned to esse which is existence and actuating presence as Schmitz argues when he says “Among [certain vital needs] the primary and governing need is the conservation of life, directly that of the individual … This original and fundamental need of preservation finds its origin and its finality in the ultimate value of existence, that primary value recognized by the transcendental property of being (esse, actus essendi) (pg. 26). Similarly, one could argue that self-preservation is proper to identity, which would be related to the transcendental res, (a thing which has a determinate character — a being or ens — “that possesses an identity that is its own, and is distinguishable from other beings” (pg. 11). Identity certainly requires unity to be a singular whole. However, since unum is the marriage of existence and essence, I believe that unum is a satisfactory transcendental that encompasses the experience of self-preservation as well as not only the union of existence and essence but also the encompassing of ens (being) and res (thing).

Aquinas acknowledged that “if appetite terminates in good and peace and the beautiful, this does not mean that it terminates in different goals. By the very fact of tending to good, a thing at the same time tends to the beautiful and to peace … It tends to the beautiful inasmuch as it is proportioned and specified in itself … Whoever tends to good, then … tends to the beautiful.” (Aquinas, 1259/1954, Q.22, Art. I, Answer #12)

Also, “… the moral values rooted fundamentally, in the good of being … most directly form us in the fulfillment and maturity of our humanity; these primarily determine the value of the exercise of responsible freedom. It is just here that our freedom is called into the service of the perfection of our humanity” (Ibid., pg. 82).

see Schindler (2017), e.g., “Plotinus identified beauty as the precise cause of love;” (pg. 335) “Love and beauty therefore perfectly coincide” (pg. 343)

Schmitz (2009), pg. 27: i.e., “… there is the need built into our humanity that expresses the relationality of being (aliquid). This interpersonal relationality acknowledges that the well-being of each of us and our associations cannot be sustained by an exaggerated, isolated individualism.”

Kreeft (2020), pgs. 75-76; Kreeft explains the extrinsic spiritual gravity in the context of love of another, and he quotes Augustine’s description of God as his “gravity”

see Aertsen (1990/1991), pgs. 70-78; Aertsen, taking a purely Thomistic perspective of unum, verum, and bonum, posits a different perspective in that “the beautiful is to be taken as the extension of the true to the good” (pg. 96) and did not need to be based on a distinct transcendental (pg. 97), but I believe truth and goodness are insufficient for drawing a person from unum to aliquid because it would be ignoring the body-soul unity regarding sense knowledge and sense appetite which integrate with the affective capacity. In other words, we sense and perceive beauty as human beings before our intellects apprehend truth in its integrity, harmony, and clarity and before we respond volitionally with corresponding goodness.

see also Kreeft (2020), pg. 37 for an explanation of how the heart intuits beauty with “inner seeing” and pgs. 181-182, e.g., “The (spiritual) heart is an epistemological organ: it does not only feel and emote and desire but it also sees, it detects truth: for instance, the truth of goodness by conscience … and the truth of beauty, by aesthetic intuition and appreciation and judgment. It sees. The most important thing it sees is God.”

see Schindler (2017) for an explanation of the necessity of beauty as a transcendental, e.g., “Given Aquinas’ own characterization of love, it turns out to be the proper correlate, not of goodness simply, or of truth simply, but of their transformative coincidence in beauty.” (pg. 344)