Additional Models of TFC Theory

Last updated 10/10/2024

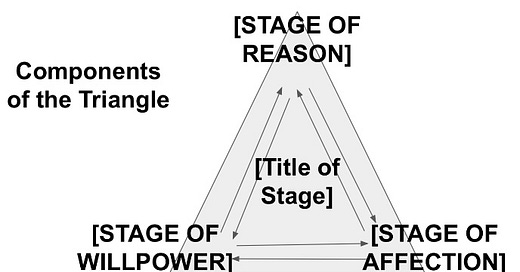

Inter-Relational Model

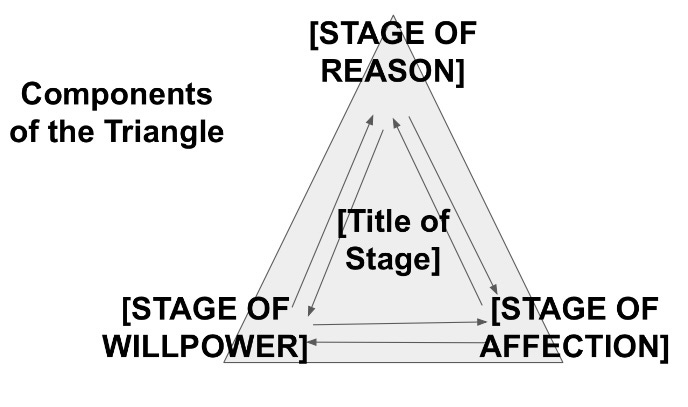

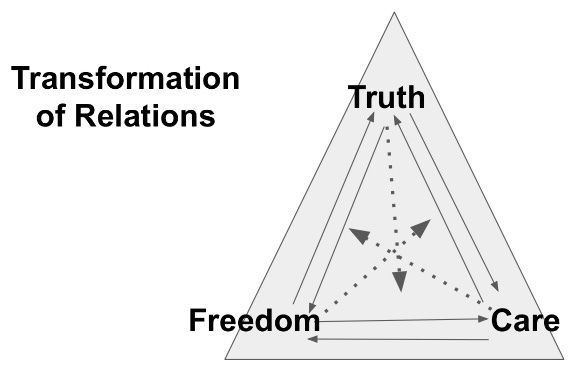

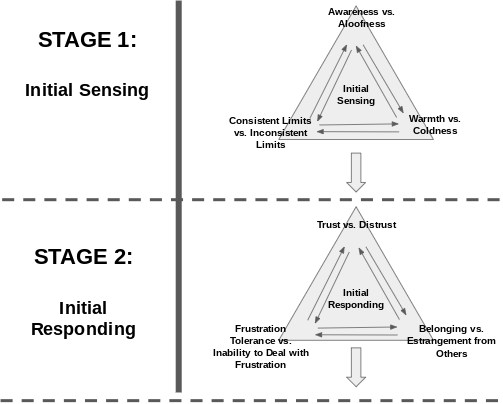

An inter-relational model may more accurately represent what is occurring both phenomenologically and behaviorally. Reason, will, and affection cannot be separated. Truth, freedom, and care cannot be separated. Inner peace, meaning, and happiness cannot be separated. They all have some relation to each other. Even more accurate may be the figures below in which there is even a relation between (1) an operation of the soul and (2) the relationship itself between the other two operations. For example, awareness can affect how consistent limits and warmth relate to one another. Otherness can affect the relationship between openness and responsible choices. Inner peace can affect how meaning and happiness relate to one another. The CCMMP gives the following example:

Consideration of the person as worthy of just treatment demands a notion of what and who the person is. This principle presupposes a deep tie between freedom and truth; that is, freedom of conscience to do the good is possible only in light of the truth of the person and of his or her life journey and ultimate and, which informs our understanding of how to relate to each person (Vitz, Nordling, & Titus, 2020, pg. 259, emphasis added).

There is a clear connection to how disrupting the “tie between freedom and truth” will directly affect the ability to care for someone. When one faculty of the soul is disordered, the rest of the faculties will be disturbed because the soul is a singularity with no parts.

Here is a concrete scenario: an adolescent boy has achieved a sufficient degree of openness, responsible choices, and otherness so he begins establishing truth, freedom, and care in his life. However, he has been exposed to pornography and begins to habitually use it as an addictive behavior. Although he is making responsible choices throughout most of the day, his freedom is impacted by this addictive habit. Also, even though he may be moving forward in truthfulness apart from his secret habit and moving forward in care (apart from caring for his own body as sacred and treating others chastely), the relationship between truth and care is disturbed through objectification of other persons. The relation of reason to affection (i.e., “this is true, therefore I should desire it” and “I sense the truth in my desires”) is impacted by his lack of willpower (i.e., “I do what I hate and I hate what I do”). The young man will be unable to reconcile a healthy relation between truthfulness and care if his inner freedom is inhibited as he moves in the direction of self-imprisonment. The same is true across each of the stages - a single disturbance has ripple effects across all the different relations. Nothing happens in isolation in our souls or in our bodies, in our minds or in our hearts.

As a scriptural example, we can see the transformation of relations in how Judas and Peter responded differently after they each betrayed Jesus. Judas lacked freedom due to his disordinate attachment to money. This prevented authentic care of his fellow man. Because of this disruption of the relation between freedom and care (i.e., my free will is meant for love), this distorted relation actually transformed the relation between care and truth. How so? When Judas betrayed Jesus, he could not confront the truth of what he had done in light of God’s mercy because he never fully allowed Christ’s mercy into his own life whether through acceptance of mercy (i.e., “Lord, please forgive me - I have been stealing from the money bag”) or extending mercy (i.e., “Brothers, we have too much in the money bag - let’s give to this widow who only gave two small coins as an offering”). Since he struggled with freedom and care, he could not see the fullness of truth - that Jesus was God and that He loved him mercifully. Peter also sinned, but here is the difference: because he experienced a greater balance and integration of truth, freedom, and care, he was eventually able to accept the mercy of God.

Another way of understanding this inter-relational framework is by examining this as a group or family dynamic. When a group of four people are together, each with individual relationships to one another, each of those individual relationships affect the other. If those four people are in the same room, the way in which they speak to one another is affected by the combined presence of all four people. If a person leaves the group, then the dynamic has changed so that there are maybe only minor word changes or a shifting in body language, or perhaps there is a complete transformation of how the person speaks altogether and seems to be a completely different person to an outside observer. Similarly, our truth, freedom, and care “speak” to one another as a collection of experiences, thoughts, and actions. When one is affected, partially absent, or particularly strong, the other two will be affected for better or for worse.

STAGES OF MATURATION IN AN INTER-RELATIONAL MODEL

Note that Stage Six is unique in that they are not so much values pursued as they are theological virtues that come from grace. God chooses to give us faith, hope, and love and we receive it. Our development, as a human person, is interpersonal with God and aimed toward God Himself as the end, though He may still transmit the necessary graces through human relationships. Uniquely, we see that God chooses some of his very young people to receive the gifts of faith, hope, and love as supernatural, or beyond natural capacities. Little children who are still working through Stage 2 may foreshadow their own fuller maturity when they begin to show their child-like trust in God born out of a child-like trust in their parents and/or caregivers that plant the seeds of faith.

Stages 5 through 7 are treated differently. Beginning with ultimate values (Stage 5) which predispose us to receive grace, and then receiving the grace (Stage 6) , which both happen predominantly during adolescence, we see a reciprocal relationship between these two stages. Then, when grace is received, a response is demanded (Stage 7) across mind, will, and heart. When we respond to grace through an integrated mind, a committed will, and faithful and life-giving heart (Stage 7), we move more in the direction of ultimate values and continue to predispose ourselves to even more grace (Stage 6), “for to everyone who has, more will be given” (Mt 25:29). Therefore, a continuous feedback loop for Stages 5 through 7 is created by which our cognitive, volitional, and affective powers mature. Ultimate values, receiving grace, and responding to grace are collectively the mechanism of maturation by which we attain transcendent union.

The Spherical Model

The steps build off of one another. The question is do they build inward toward the center of the person or do they build outward from the center. For example, is warmth (the beginning stage of the heart) the core of belonging, care, etc. fidelity, happiness, or is happiness the core of warmth, belonging, self-worth, etc. The evidence seems to strongly support that inner peace, meaning, and happiness are core to our personhood so all other stages would be sequentially working inward deeper into our mystery until we reach the center where God is inviting us to be in transcendent union with Him. However, we also know that working inward requires healthy development of the outer layers of our psychology (i.e., being drawn deeper into the world through awareness, trust, security, openness, etc.). This is an image in order to illustrate the spiritual nature of the stages as a journey inward to God, but does that imply that we turn to ourselves? No. The whole point is that it is a journey to God Who lives in us at our center, but we also journey outward to live in Him, and as He lives in the hearts of other persons, through our thoughts, words, and deeds.

If the heart is our center, why is affection on the outside working inward? It is because interpersonal and intrapersonal affection develop just as reason and willpower do. Then we might object: shouldn’t I (the personal unity of my heart) be at the center of my soul? I would answer that the heart is the center of your soul, but God is meant to be united in relationship to the “you” of your heart (pulchrum united in aliquid to your unum). Truthfully, I lack the brilliance to illustrate this in full. No singular diagram can depict the soul which I must continually repeat is simple with no parts. The benefit here in attempting to do so is that we recognize that transcendence is not limited to union with God Who is outside of existence, but rather we are called to union with Him as He is mysteriously within the depths of our personal existence. St. Augustine poetically prays: “Yet all the time You were more inward than the most inward place of my heart and loftier than the highest” (Augustine (401/2017), III.VI, pg. 50). I believe the latter reality is of more practical import for psycho-spiritual development. St. Paul preaches “Indeed he is not far from any one of us. For ‘In him we live and move and have our being’” (Acts 17:27b-28a).1 He is the heart of our hearts and the center of our soul.

Model of Triune Convergence

One of the seemingly inconsistent features of Azcárate’s theory is that there are affective and interpersonal features in the development of reason (i.e., interpersonal awareness, trust, security, openness, and truth, as well as the affection of peace). Likewise, there are cognitive aspects in the development of the will (i.e., consistent limits lay a foundation for perceiving reality) and volitive overlap in the development of the affection (i.e., fidelity itself describes commitment in addition to the affective element of fidelity). This makes sense as we are simple souls with no parts. Should we be surprised that there is overlap across these three intentionalities? In fact, the fullness of love requires all three intentionalities.

Part of the process of theosis (the teaching that we become more and more like God; “divinization”) should include becoming simpler, more integrated, and more unified in our consciousness. Therefore, inspired heavily by both the doctrine of Divine Simplicity and Dr. Tallon’s Theory of Triune Consciousness (affectivity, cognition, and volition being one, triune consciousness), I created this representation of the Maturation vs. Estrangement Growth Chart to visualize how this process takes place.

In summary, as we develop, our affection becomes more cognitive and volitional; our volition becomes cognitive and affective; our cognition becomes more volitional and affective.

References

Augustine (2017). Confessions. Translation by F. J. Sheed (1942/1943). Word on Fire Catholic Ministries: Park Ridge, IL (Original work composed 397-401)

Azcarate, E. M. (1979). Maturation vs. Estrangement Growth Chart.

Tallon, A. (1997). Head and Heart: Affection, Cognition, Volition as Triune Consciousness. Fordham University Press: New York, NY

Vitz, P., Nordling, W. J., & Titus, C. S. (2020). A Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person: Integration with Psychology & Mental Health Practice. Divine Mercy University Press: Sterling, VA

St. Paul is possibly quoting Epimenides of Knossos (6th century B.C.)